Anonymizing Qualitative Data

By Janet Salmons, Ph.D.

Dr. Salmons is the author of Doing Qualitative Research Online, and Gather Your Data Online. Use the code COMMUNIT24 for 25% off through December 31, 2024 if you purchase research books from Sage.

Protect Participants’ Identities

Qualitative researchers often collect very personal data, whether in interviews or in narratives, diaries, or other records that depict their experiences. One way to protect their identities is by changing their names, and anonymizing the data. Gibbs (2018) suggests an approach:

As you will eventually be quoting from your transcripts in your write up of the research and you might even be depositing the data in a public archive so other researchers have access to it you will need to consider how you will ensure confidentiality. Do this by anonymizing the names of people and places to make it safe for participants (if their activities are illegal or illicit) and safe for the researcher (e.g. if you have been investigating covert operations or paramilitary groups). It is easiest to produce an anonymized copy immediately after transcription. However, you may find it is best to do your analysis using the unanonymized version, as familiarity with the real names and places can make it easier. However, many researchers report that if you anonymize early on in the analysis, you soon become just as familiar with the anonymized names.

Create a listing, in a separate file, kept somewhere safe, of all the names – people, places, organizations, companies, products – that you have changed and what you have substituted for them. Use search and find in your word processor to find each name and substitute it with the anonymized version. Make sure you search for both normal text versions of respondent’s names (‘Mary’) if these appear in other respondent’s talk as well as capitalized versions (‘MARY:’) if you have used that to identify speakers. It is usually best to use pseudonyms rather than crude blanks, asterisks, code numbers and so on. You will still need to read the transcript carefully to ensure that more subtle, but obvious clues to a person, place or institution are not evident. If you are going to deposit your data into a data archive, then remember you will need to retain and deposit the original, unanonymized versions alongside the accessible anonymized versions.

Gibbs, G. (2018). Data preparation. In Analyzing Qualitative Data ( Second ed., pp. 17-36). SAGE Publications Ltd, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526441867

What Type of Textual Data Must Be Anonymized for Research?

Learn more about anonymizing the data in these open-access articles:

Brear, M. (2018). Swazi co-researcher participants’ dynamic preferences and motivations for, representation with real names and (English-language) pseudonyms – an ethnography. Qualitative Research, 18(6), 722–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117743467

Abstract. Using pseudonyms is the accepted and expected ethical practice for maintaining participants’ privacy in qualitative research. However it may not always be ethical, for example in participatory action research (PAR), where academics aim to recognise co-researcher participants’ contributions. I used Bourdieusian theory to analyse data detailing deliberations about, and the dynamic pseudonym-related preferences of, 10 co-researcher participants, generated through an ethnography of PAR in rural Swaziland. The analysis demonstrates the salience of engaging participants in careful deliberations about pseudonyms and the racism and privilege inherent to the practice of White (or otherwise powerful) academics researching and representing non-White (or otherwise marginalized) participants. It further highlights practical strategies academics might employ to facilitate ethical and potentially transformative deliberations with their research participants about pseudonyms, which unmask this racism and privilege.

Gerrard, Y. (2021). What’s in a (pseudo)name? Ethical conundrums for the principles of anonymisation in social media research. Qualitative Research, 21(5), 686–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120922070

Abstract. Scholars from wide-ranging disciplines are turning to social media platforms as research sites, and as platforms expand their communicative possibilities, they create more spaces for users to enact a multitude of identities. Most platforms allow users to have ‘pseudonymous’ identities; that is, they can engage in practices intended to facilitate nonidentifiable content. But pseudonymity presents a series of unique challenges to the principles of anonymisation in qualitative research. This article explores the slippery nature of dealing with pseudonymous social media users’ personally identifiable data during research, framed around my responses to four questions I was asked when I applied for ethical approval to conduct research with pseudonymous fan communities on social media. The four questions concern: (Q1) changing notions of ‘public’ and ‘private’ forms of data; (Q2) identifying underage and therefore vulnerable participants online; (Q3) changes to the processes of obtaining informed consent from social media users; and (Q4) the risks social media research might bring to those conducting it. This article concludes by calling for qualitative researchers and Ethics Review Boards (ERBs) to engage with institutional ethics review across the duration of a project, or at the very least to advocate for ongoing consent as research progresses, especially for (but certainly not limited to) research involving pseudonymous social media users. The article aims to be useful to other researchers facing similar dilemmas. Indeed, given the popularity of pseudonymity on social media and the growing penetration of platforms across global demographics, a need for ethical discussions of this kind is surely set to increase.

Heaton, J. (2022). “*Pseudonyms Are Used Throughout”: A Footnote, Unpacked. Qualitative Inquiry, 28(1), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004211048379

Abstract. Pseudonyms are often used to de-identify participants and other people, organizations and places mentioned in interviews and other textual data collected for research purposes. While this is commonplace, the rationale for, and limits of, using pseudonyms or other methods to disguise identifying information are seldom explained in empirical works. Following an illustrated outline of pseudonyms, epithets, codenames and other obscurant techniques used in the social sciences and humanities, this paper considers how they variously frame the identities of, and position the relations between, participants and researchers. It suggests ways in which researchers might improve on current practice.

Abstract. Itzik, L., & Walsh, S. D. (2023). Giving Them a Choice: Qualitative Research Participants Chosen Pseudonyms as a Reflection of Self-Identity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 54(6-7), 705-721. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221231193146

Abstract. The use of pseudonyms in qualitative research is common and aims to preserve the anonymity of the participants. However, there is a lack of consensus on how pseudonyms should be chosen in qualitative research among ethnic populations. The present study examines how transferring the decision as to the choice of the pseudonym to the participants themselves can illuminate aspects of their identity. The study is based on semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted with 36 young Israeli-Ethiopians. Two main themes emerged from the data which we felt were relevant to the issue of pseudonym choice: The first concerned the declarations of identity (Ethiopian, Israeli, and integrated) of the young people in the study, and the second concerned their choice of pseudonyms (in Hebrew or Amharic). Most participants chose Hebrew pseudonyms. The discussion suggests two identity profiles—Reactive and Agency—that correspond to the relationship between the identity declaration and the pseudonym chosen.

Lahman, M. K. E., Thomas, R., & Teman, E. D. (2023). A Good Name: Pseudonyms in Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 29(6), 678–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004221134088 (not open access)

Abstract. People’s names and the places, animals, and items named by people are deeply personal and reflective of their culture and identity, yet in qualitative research, the standard is to use pseudonyms. This practice is thought to protect research participants, but when are “real” names most respectful and appropriate? How might researchers include research participants in these considerations? The purpose of this methodological article is to increase transparency and collaboration around the participant naming process, bringing much-needed attention to issues of power in the naming process in research. The authors review the literature and detail their reflexive engagement with pseudonyms; they advance issues for consideration and provide recommendations in the areas of power in participant naming, culturally responsive research, and pseudonym use with trans people and incarcerated people. Throughout the article, the authors interrupt the text with reflexive narrative interludes to share personal experiences with naming.

Lange, B. P., Zaretsky, E., & Euler, H. A. (2016). Pseudo Names Are More Than Hollow Words: Sex Differences in the Choice of Pseudonyms. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 35(3), 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X15587102

Abstract. Many studies demonstrate sex differences in communication. We investigated whether also pseudonyms used in anonymity revealed the sex of the pseudonym user and whether male and female pseudonyms were perceived differently regarding sex-typical attributes (partially taken from the Bem Sex-Role Inventory), the Big Five, and creativity. Pseudonyms chosen by 19 men and 19 women were randomly selected from a list of 2,096 pseudonyms used in written university tests and then rated by a total number of 346 participants (41% men) on the above-mentioned attributes. Results showed that the pseudonym users’ sex was guessed correctly above chance. Male more than female pseudonyms were perceived as showy, aggressive, self-reliant, extrovert, and creative. Female pseudonyms were rated higher on the attributes cute, peaceful, romantic, and agreeable. We further found sex differences with respect to linguistic patterns (e.g., pseudonym length) that were, however, able to explain neither guessed sex, nor the higher creativity ratings for male pseudonyms. We conclude that even single words are used by individuals to infer significant information (e.g., sex) about their users.

Saunders, B., Kitzinger, J., & Kitzinger, C. (2015). Anonymising interview data: challenges and compromise in practice. Qualitative Research, 15(5), 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114550439

Abstract. Anonymising qualitative research data can be challenging, especially in highly sensitive contexts such as catastrophic brain injury and end-of-life decision-making. Using examples from in-depth interviews with family members of people in vegetative and minimally conscious states, this article discusses the issues we faced in trying to maximise participant anonymity alongside maintaining the integrity of our data. We discuss how we developed elaborate, context-sensitive strategies to try to preserve the richness of the interview material wherever possible while also protecting participants. This discussion of the practical and ethical details of anonymising is designed to add to the largely theoretical literature on this topic and to be of illustrative use to other researchers confronting similar dilemmas.

Tilley, L., & Woodthorpe, K. (2011). Is it the end for anonymity as we know it? A critical examination of the ethical principle of anonymity in the context of 21st century demands on the qualitative researcher. Qualitative Research, 11(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794110394073

Abstract. Told from the perspective of two UK-based early career researchers, this article is an examination of contemporary challenges posed when dealing with the ethical principle of anonymity in qualitative research, specifically at the point of dissemination. Drawing on their respective doctoral experience and literature exploring the difficulties that can arise from the application of anonymity with regard to historical and geographical contexts, the authors question the applicability of the principle of anonymity alongside pressures to disseminate widely. In so doing, the article considers anonymity in relation to the following: demonstrating value for money to funders; being accountable to stakeholders; involvement in knowledge transfer; and the demands of putting as much information ‘out there’ as possible, particularly on the internet. In light of these pressures, the article suggests that the standard of anonymity in the context of the 21st century academic world may need to be rethought.

Vainio, A. (2013). Beyond research ethics: anonymity as ‘ontology’, ‘analysis’ and ‘independence.’ Qualitative Research, 13(6), 685–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112459669

Abstract. Anonymity – its desirability and perceived difficulty divides the domain of qualitative research. This article shows that such divisions are associated with discrepancies in assumptions about what the power relations between the researcher and the researched, as well as the desired goals of the research, should be. This article questions the assumption that anonymity is necessary only for ethical reasons and identifies three additional functions of it in qualitative research: anonymity as ‘ontology’, anonymity as ‘analysis’ and anonymity as ‘independence’. First, ontologically, anonymity is a way of turning into ‘data’ what someone has said or written. Second, anonymization as ‘analysis’ turns the participants into examples of specific theoretical categories, and as such is a part of the data analysis. Third, anonymity as ‘independence’ enables the researcher to interpret the data irrespective of the participants’ wishes. As a conclusion, this article argues that anonymizing research participants has an influence on the overall quality of research and therefore is also useful when no ethical risks are perceived, when participants wish not to remain anonymous or when their anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

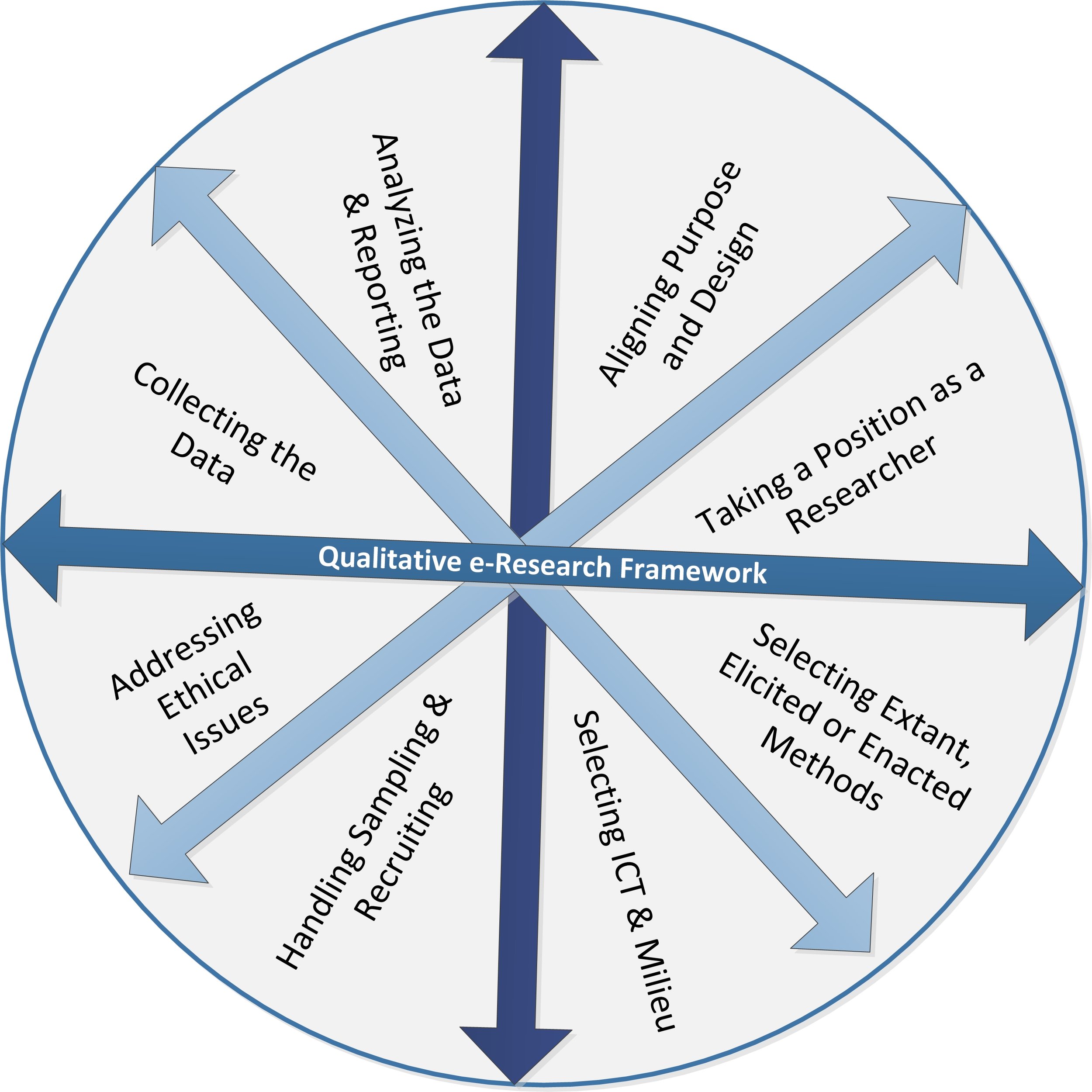

The wealth of material available online is irresistible to social researchers who are trying to understand contemporary experiences, perspectives, and events. The ethical collection and -use of such material is anything but straightforward. Find open-access articles that explore different approaches.