Big Data rich and Big Data poor

“Data is the new oil.” Clive Humby, mathematician and architect of Tesco’s Clubcard, is credited with saying this first in 2006, and it’s been repeated numerous times in the last decade. The comparison between data and oil refers to its value being extracted through refinement; or in the case of data, through analysis. Unlike oil, data is being created at a faster pace than it can be consumed, or analysed. We’re awash with data. You may have heard it said that “90% of all the data in the world has been generated over the last two years.” Or, as Hal R. Varian, Chief Economist at Google, puts it another way: “A billion hours ago, modern homo sapiens emerged. A billion minutes ago, Christianity began. A billion seconds ago, the IBM PC was released. A billion Google searches ago … was this morning.”

The capacity to collect and analyse massive datasets has already transformed fields such as biology, astronomy, and physics, and for many, the ‘big data revolution’ promises to ask, and help us answer, fundamental questions about individuals and collectives. But who gets access to all this data we’re producing through our increasingly networked and digital lives, and for what purpose?

Image credit: Divided by David Wan. This work is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Image credit: Divided by David Wan. This work is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 license.

In 2012, danah boyd and Kate Crawford offered a provocation that the limited access to big data was creating a new digital divide between “the Big Data rich and the Big Data poor.” It’s only companies, and the social scientists working within these companies, that have access to really large social and transactional datasets. The broader scholarly community usually does not because companies refuse to release it or because purchasing it costs too much.

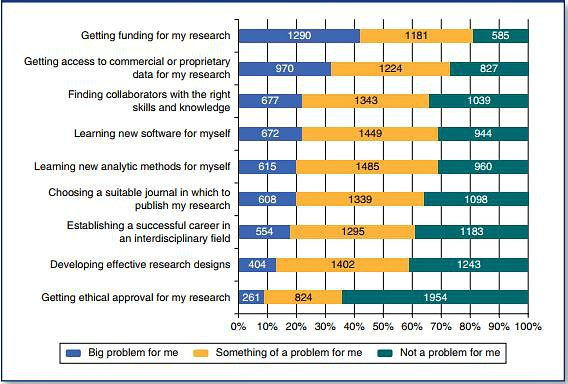

Recently, I conducted a survey of more than 9,000 social scientists to learn more about researchers who are engaged in research using big data and the challenges they face, as well as the barriers to entry for those looking to do this kind of research in the future. 32 per cent of respondents who are currently engaged in big data research reported that getting access to commercial or proprietary data was a “big problem” for them:

Figure 1: Challenges facing big data researchers (n = 2273)

Figure 1: Challenges facing big data researchers (n = 2273)

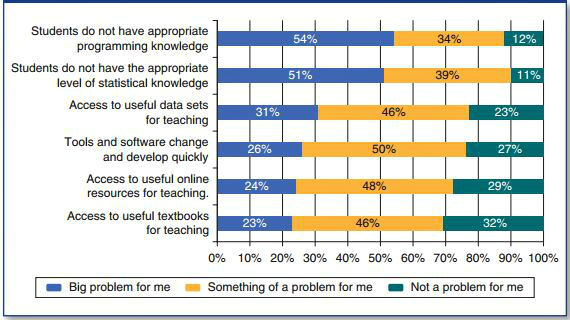

But it isn’t only the question of who can access data that leads to divides. As boyd and Crawford point out, and our survey supports, there is also a skills gap holding social science back: the level of quantitative and programming skills required for big data research make it a challenge for educators to introduce it into traditional social science degree courses as there is little time or expertise amongst teaching faculty:

Figure 2: Challenges facing educators teaching big data (n = 1212)

Figure 2: Challenges facing educators teaching big data (n = 1212)

Why does it matter?

So who cares if academic social scientists can’t do big data, either because they can’t access the data and/or don’t have the skills they need to engage with it? Why not just have companies like Twitter and Facebook analysing social media data? Some have even gone so as far as to argue that academics should not engage in research that can be done better by industry.

There are a couple of reasons why this is problematic. Firstly, because replication is the engine of science, and irreproducible research slows progress. If only researchers within companies can access and analyse big social datasets, “those without access can neither reproduce nor evaluate the methodological claims of those who have privileged access”.

And secondly, and arguably most importantly, the motivations of industry researchers and social scientists may differ in ways that may really matter. Big data research conducted by companies is usually in service of a single overarching goal: to sell you more stuff. Social scientists with the right skills and access to the right data may use their research to contribute to the body of knowledge, with the aim of better understanding and improving social outcomes.

The questions boyd and Crawford pose at the start of their paper summarize this perfectly. They ask:

“Will large-scale search data help us create better tools, services, and public goods? Or will it usher in a new wave of privacy incursions and invasive marketing? Will data analytics help us understand online communities and political movements? Or will it be used to track protesters and suppress speech? Will it transform how we study human communication and culture, or narrow the palette of research options and alter what ‘research’ means?”

As of yet, the answers to these important questions are unclear.