Euro CSS 2019: European Symposium Series on Societal Challenges in Computational Social Science

The 2nd-4th September 2019 marked the third in a series of symposia on Societal Challenges in Computational Social Science (Euro CSS). Computer scientists, political scientists, sociologists, physicists, mathematicians and psychologists from 24 countries gathered in Zurich for a day of workshops and tutorials followed by a two-day one track conference.

This year’s theme was Polarization and Radicalization. ‘We couldn’t have predicted how relevant this topic would be when we submitted our proposal in 2016’, says Frank Schweitzer in introducing the first day of talks. In the context of changing political landscapes in several countries worldwide, ‘we are here to discuss scientific methods to better understand these topics.’

As well as soaking up the huge variety of presentations and discussions around disinformation, censorship, populism and political polarization, we were delighted to sponsor the Best Presentation award, which went to Theresa Gessler, Gergo Toth and Johannes Wachs for their work on how exposure to refugees has influenced attitudes to immigration in Hungary. They showed how during the 2015 migrant crisis, exposure to refugees in their own country galvanized opposition to immigration, with their results predicting the anti-immigration outcome of the country’s 2016 referendum.

Should we stop talking about echo chambers?

So we were here to talk about polarization, but what does that actually mean? Pawel Sobkowicz noted that we currently have no standardized way to model polarization, and the meaning of the term itself was hotly debated in Monday’s workshops. While we tend to associate extremism with the idea of polarization, Andreas Flache noted in his keynote that political opinions in the US at least are becoming not more extreme, but more consistent.

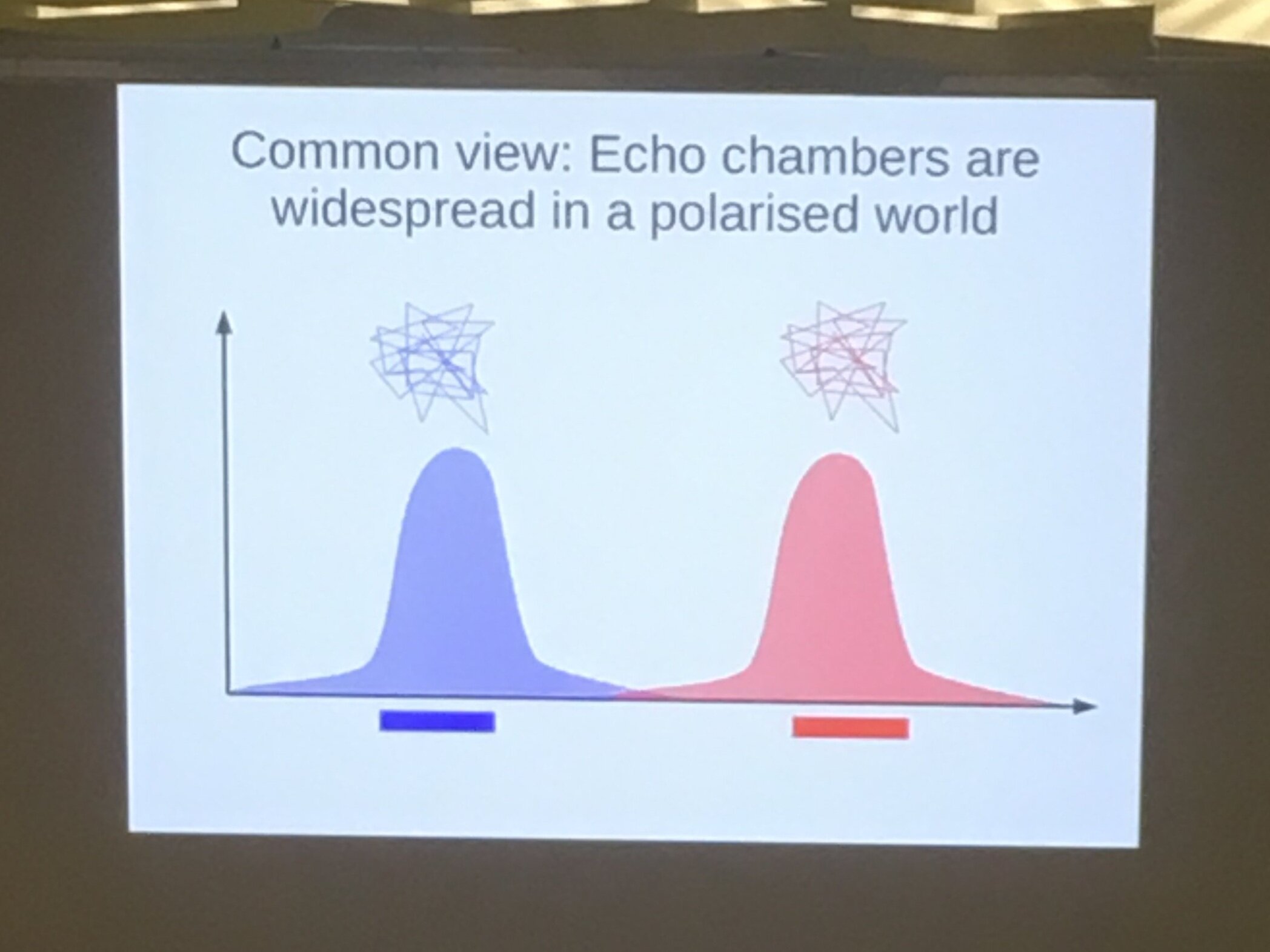

What many agreed on is that we need to forget about the concept of echo chambers in a polarized world. While we’re used to hearing about the idea of people getting lost in filter bubbles online, confronted only with opinions that reinforce their own beliefs, Axel Bruns in his discussion of Philip Leifeld’s keynote nonsensed this notion. In a passionate talk he pointed out that polarization is an inherently communicative phenomenon, i.e., if we had no exposure to views that oppose our own, it would be impossible for our own to become polarized.

Hywel Williams, who collected every tweet containing the word ‘Brexit’ in 2018 (all 16.4M of them), showed us that rather than isolated Twitter bubbles, we more commonly see a consistent peak of sentiment at the moderate middle. In fact, the heavily polarized tweets made up only a tiny percentage of Brexit-related tweets that year.

Clemens Jarnach, too, presented perhaps unexpected findings showing that news consumption during the Brexit campaign was not as polarized between Remainers and Leavers as you might expect; both groups got most of their news from the BBC and other main outlets, and most had a diverse media diet.

Collaboration and mixed methods

In her keynote Disinformation in context: Understanding qualitative approaches to social media manipulation, Alice E. Marwick reminded us of the value of incorporating qualitative methods in computational social science. Qualitative methods can answer questions raised by quantitative ones, and vice versa. A mixed methods approach helps us to identify and understand the real people behind the numbers. It can help us understand, for example, what motivates people to share ‘fake news’.

Continuing in this vein, Jürgen Pfeffer closed the first day of talks by asking, ‘so what’? We know that online manipulation of truth exists, but how do we measure the real-world impact of this - if there even is one? Do our online interactions actually have the power to affect our beliefs and behaviors offline? Turns out they do. It only took a week of interacting on Twitter with people with opposing political views for his experiment’s participants to become more polarized towards their own existing view.

So people’s online interactions affect their behavior offline; maybe social media is changing how mainstream media reports, too? Reassuringly, a research project led by Silke Adam has demonstrated that at least in Germany, reporting by mainstream media hasn’t changed as a result of online communication.

The final day was wrapped up with an engaging keynote on online hate speech from Helen Margetts. If we want to effectively tackle hate speech, collaboration is absolutely key—between policy-makers and researchers, between different social media platforms, and across disciplinary lines. When it comes to detecting hate speech online, she says, ‘deep learning simply can’t manage without the input of social science.’

Despite the challenges involved in tackling online abuse, we ended on a high note: Helen observed that a shift has occurred, with policy-makers now actively seeking to collaborate with social scientists, and recognizing the urgent need for research in this area.

Check out our #EuroCSS highlights on Twitter

We want to thank the organizers for this timely and brilliantly varied event, and to everyone who contributed to make it a brilliant few days of developing our understanding of the power of computational social science to address societal issues worldwide.