Make Sure Your Book is Findable! Advice on Discoverability

Despite the warnings of digital doomsayers, academic book publishing remains dominated by print. That said, reader behavior has changed and continues to evolve. This is particularly true of how readers discover and read books and chapters. Rather than visiting a library or bookshop in person, readers of scholarly books start their searches online. For publishers, ensuring that books are prominent and visible in such searches is essential to encourage readership and drive citations.

Libraries have also evolved. Purchasing a book “just in case” a user wants to read it in the future is no longer standard practice. Rather, libraries list available books and make a purchase “just in time” to meet the user’s needs. This process is known as demand (or patron-) driven acquisition. It has been a “game-changer” for everyone involved in academic publishing. This change, from “just in case” to “just in time”, means that books won’t be bought if they can’t be found online by the end user.

The key activity for a publisher in this reality is to ensure that their books are available and visible to readers. It is in making books discoverable that publishers can now connect author and reader. The role of a publisher in facilitating discoverability involves three pillars:

Bibliographic metadata – this includes a DOI (Digital Object Identifier), ORCIDs (Open Researcher and Contributor ID), the publication date, the title)

Semantic metadata – this is beyond simple metadata (information about a book). Semantic enrichment creates another information layer; for example with abstracts and keywords. This “enriched” metadata returns more accurate searches. If this sounds complicated, it’s because it is!

Granularity – information about chapters can be important alongside information about the entire book.

The post can originally be on LSE Impact Blog under the title:

"Make sure your book is discoverable! Advice for the reader-oriented author" by Terry Clague.

Impact Blog Logo

Search engine optimization is also significant when it comes to amplifying the above activities. A good publisher will optimize the content of their books for discovery through search engines like Google. For scholarly publishers, operating at scale ensures a dependable, diverse, discoverable range of books but also enables essential investment in technology.

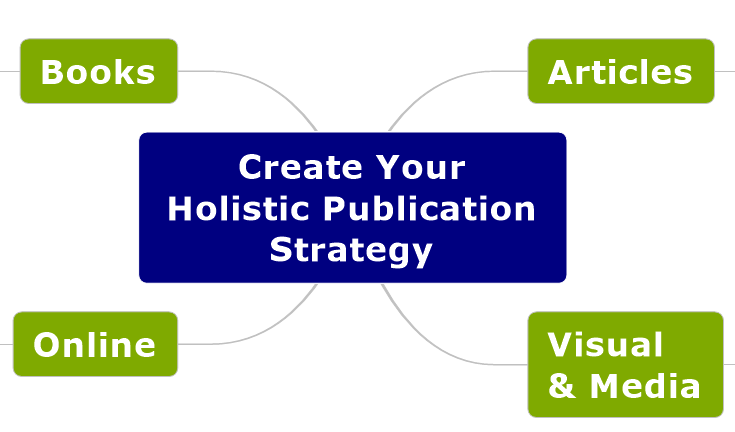

Publishers and authors share many of the same goals in publishing books – both thrive by ensuring books are widely available and discovered. Given these mutually beneficial outcomes, it makes sense to collaborate to maximize chances of success. Authors can contribute to the success of their book by considering the advice of publishing professionals in crafting and developing their work. The following advice is based on the experience of studying sales and usage reports over the years and discussing these figures with colleagues and authors to try to understand the critical success factors behind successful scholarly books.

Title

The main title of the book should position it clearly, ideally without reference to further information. There is evidence that shorter titles are more likely to be cited, and also much to learn from the world of journals.

DO:

agree a concise main title that includes key positioning terms.

use the subtitle to signal the approach/coverage (textbooks often don’t need a subtitle).

ensure that a textbook title is in line with the relevant course/module title.

DON’T:

use hyphens or abbreviations unless unavoidable.

employ quotation or question marks.

attempt humour (it doesn’t travel) or try to be enigmatic!

Chapter titles

Potential readers are increasingly likely to discover a book via one of its chapters. Therefore, each chapter title should ideally be understood in isolation from the rest of the book.

DO:

think about the chapter title as an opportunity to attract readers.

consider how the title will appear to someone scanning Google Scholar, for example.

ask a colleague to look at the table of contents to get a first-glance impression.

feel empowered, as an editor, to advise contributors on their chapter titles.

DON’T:

use hyphens or abbreviations unless unavoidable.

try to be too clever – the place for that is in the content of the chapters!

Chapter abstracts

Creating a concise overview of the contents of a chapter is akin to writing a blurb for a book. If well-executed, the abstract will communicate the purpose/scope of the chapter leaving a curiosity gap that encourages readers to delve further.

DO:

work hard to craft an abstract that requires little specialist knowledge.

communicate the core message/scope of the book in the first 155 characters (i.e. the text that will display in the Google search results).

communicate the core message of the chapter, its aims and results, where possible.

DON’T:

just copy and paste the first paragraph of the chapter.

pad the abstract with value judgments.

include references.

Reader engagement

A book is not a journal issue. Whilst publishers are keen to learn from journals, it’s vital that the unique qualities associated with books are understood. Thus, authors are well-served by ensuring that chapters link together, are consistent in their quality and structure, and encourage time-pressed readers to read more. For edited volumes, such contributor solidarity ensures that a book is more than the sum of its parts.

DO:

take a step back and consider your readers regularly.

employ consistent features for each chapter.

ensure that chapters are readable in isolation with hooks to the rest of the book.

DON’T:

forget to cross reference between chapters.

expect readers to cite your book if they can’t make it through to the end!

Look candidly at your unfinished project. Is it a stepping stone, and completion will be allow you to move ahead? Or is it an obstacle that prevents you from moving forward? Find ideas to help you determine whether to revive that piece of writing or let it go.