Sampling Flaws Upset 2016 Election Polling Predictions

In statistics, a random sample is the cornerstone of any analysis. By ‘random,’ statisticians mean that the units of analysis (often people) are selected blindfold from the target population the researcher would like to say something about.When polling political party preferences, random samples are also used, but sometimes things go wrong because the population sampled from differs from the target population. In the weeks before the 2016 U.S. presidential elections took place, most polls predicted favorable odds for Hillary Clinton to become the first female president of the United States. Why did they go wrong? Well, they went wrong in four states: Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida, holding 75 electoral votes in total, all of which went to Trump and made him the winner of the election. Most probably the samples in those four states suffered the most from a small but relevant selection bias. The reason lies in the small electoral margins, i.e., difference between the number of Democratic votes and the number of Republican voters.In our research we first sampled (sample size 1,500, number of samples 4 million) from the people who actually voted on Election Day. The resulting odds were 7 to 3 in favor of Donald Trump. If we randomly sampled from a population that had a slight 1 percent selection bias towards the Democrats, the odds were also 7 to 3, but this time in favor of Hillary Clinton!So, most probably the polls sampled randomly from a population of US citizens who had the intention to vote and missed out on a small but relevant part of Republican voters, who refused to give an answer or made up their minds on Election Day itself. We summarized our outcomes in an 8-minute YouTube clip as well.https://youtu.be/HpLoxfKioUc What does this mean going forward?Future polls should invest more in high-quality samples in the swing states, i.e., the ones with the smallest electoral margins. But honesty dictates that even high-quality samples, with no under representation of the lower educated, may not have prevented this mishap. They asked for the respondents’ political party preference at that point in time. However, people (Republicans more than Democrats) only revealed their preference on Election Day itself. Maybe the takeaway is that the media and the pollster should be a little less self-assured when presenting yet another poll… At best it is an estimate of the state of affairs at that point in time. There is also the danger of a self-destroying prophecy – i.e. if polls keep telling Clinton is going to win by a wide margin, then Democrats may stay at home on the election day.

Why did they go wrong? Well, they went wrong in four states: Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida, holding 75 electoral votes in total, all of which went to Trump and made him the winner of the election. Most probably the samples in those four states suffered the most from a small but relevant selection bias. The reason lies in the small electoral margins, i.e., difference between the number of Democratic votes and the number of Republican voters.In our research we first sampled (sample size 1,500, number of samples 4 million) from the people who actually voted on Election Day. The resulting odds were 7 to 3 in favor of Donald Trump. If we randomly sampled from a population that had a slight 1 percent selection bias towards the Democrats, the odds were also 7 to 3, but this time in favor of Hillary Clinton!So, most probably the polls sampled randomly from a population of US citizens who had the intention to vote and missed out on a small but relevant part of Republican voters, who refused to give an answer or made up their minds on Election Day itself. We summarized our outcomes in an 8-minute YouTube clip as well.https://youtu.be/HpLoxfKioUc What does this mean going forward?Future polls should invest more in high-quality samples in the swing states, i.e., the ones with the smallest electoral margins. But honesty dictates that even high-quality samples, with no under representation of the lower educated, may not have prevented this mishap. They asked for the respondents’ political party preference at that point in time. However, people (Republicans more than Democrats) only revealed their preference on Election Day itself. Maybe the takeaway is that the media and the pollster should be a little less self-assured when presenting yet another poll… At best it is an estimate of the state of affairs at that point in time. There is also the danger of a self-destroying prophecy – i.e. if polls keep telling Clinton is going to win by a wide margin, then Democrats may stay at home on the election day.

***

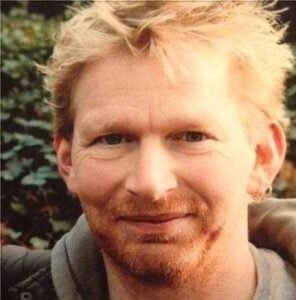

Manfred te Grotenhuis, an associate professor of quantitative data analysis at Radboud University Nijmegen, is the author of two SAGE Publishing textbooks, Basic SPSS Tutorial and How to Use SPSS Syntax.