Social network analysis of the 2017 "Summer of Hate"

By Megan Squire, Professor of Computer Science, Elon University

Fifty years after the "Summer of Love" transformed American youth culture, Andrew Anglin, the proprietor of the neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer, announced to his followers that the summer of 2017 would be "The Summer of Hate." Throughout that summer, extremist far-right groups in the United States used social networking sites, including Facebook, to plan "free speech" rallies, anti-Muslim demonstrations, and rallies to protest removal of Confederate monuments.

The Summer of Hate reached its nadir on the weekend of August 11 and 12, when hundreds of far-right extremists, including neo-Nazis, white supremacists, Ku Klux Klan members, and militia members gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia for an event organized on Facebook and billed as an attempt to "unite the right".

As a researcher watching this event being planned on Facebook, I wondered just how "united" this event would be. Who is going to this thing? Which extremist groups do those people align with?

To answer these questions, I wrote software to access the (public and freely accessible at the time) Facebook Graph application programming interface (API) to create a large dataset of publicly-accessible membership rosters for 1,870 different English-language and US-focused far-right groups and events. I used a combination of five methods for finding groups and events: manual keyword searching, automating the Search API, using the "Suggested Groups" feature within Facebook, finding Facebook Groups attached to Facebook Pages, and accessing the public group lists attached to the timelines of known extremist group leaders.

I then organized these groups into 10 far-right categories corresponding to their primary identity or belief system. Examples of these ideologies include white nationalist, neo-Nazi, Alt-Right, neo-Confederate, and so on. Descriptions of each ideology or group identity come from two US-based not-for-profit extremist monitoring groups: The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). The primary ideological category for each group or event was determined by evaluating its name, its description, its cover photo, and in some cases looking at how the group had been described in its own marketing materials, by groups such as SPLC and ADL, and in the news media.

Sometimes it was difficult to choose just one ideology for a group, especially since so many groups have a mixture of white supremacist, anti-Semitic, nativist, or misogynist beliefs. At the same time, many newer groups were still working on defining their beliefs. I am grateful to two panels of experts from two different extremist monitoring groups who worked with me to flesh out each ideology and help to correctly categorize groups.

After dividing all the groups based on their ideological designation, it was time to understand more about how the different groups and ideologies interact with each other. To assist with this task, I wrote a small program to calculate how many members were shared in common between every pair of groups (i.e. how many users in group A are also in group B, how many in group A are also in group C, and so on).

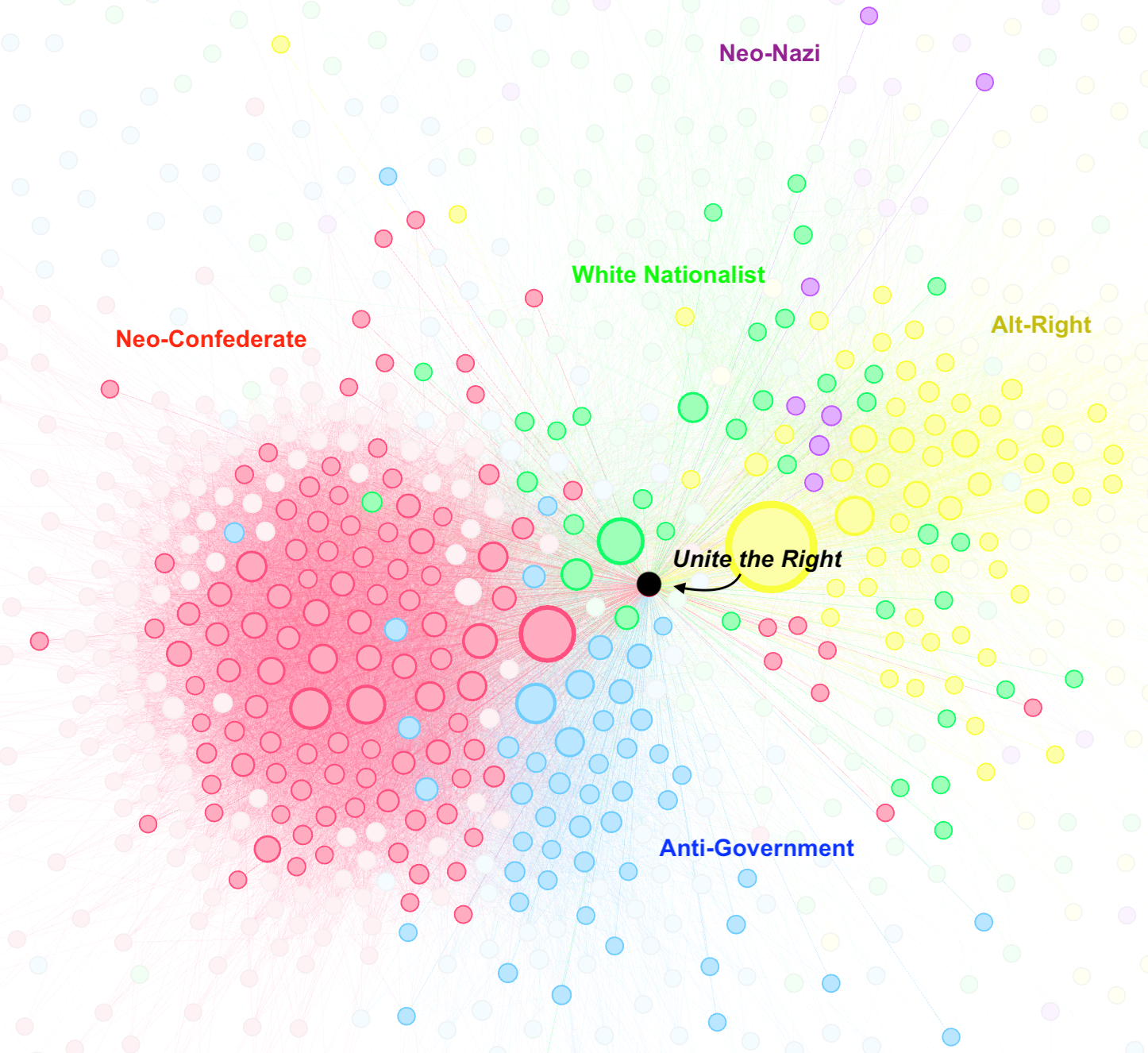

Finally, I used social network analysis techniques to begin to analyze the co-membership between these Facebook groups. I used Gephi network analysis software to visualize each Facebook group as a node on a graph. Groups are shown as connected to one another on the graph if they share more than 10 members in common.

The graph below shows around 700 groups from just five of the ten ideologies in my data set. For this study I chose to include five ideologies that were particularly prominent at the Unite the Right event: White Nationalists, Alt-Right, Anti-Government "Patriot" Militias, Neo-Confederates, and Neo-Nazis.

I directed the software to use a display algorithm that places nodes closer together if they share more members in common, and that would put nodes at the center of a diagram based on how many nodes connect to them. Groups with more members are also shown with larger circles. For example, the large yellow circle near the middle of the diagram is a very large Facebook group dedicated to sharing alt-right memes.

Interestingly, the Unite the Right event is shown in the very center of the graph—I changed its color to black to make it easier to see.

Based on this graph, we begin to see that there are some ideologies which are more inclined to share membership (for instance, Neo-Confederates with militias, and Alt-Right with white nationalists). At the same time, there are other ideologies which are less inclined to share membership, for example Alt-Right with Neo-Confederates.

To understand more about the various ideological connections to Unite the Right in particular, we can isolate its portion of the graph and visualize only the nodes that are connected to this event. In the diagram below, the groups that share members with the Unite the Right roster are shown in bright colors, while nodes that were not attached to Unite the Right fade into the background.

It is not surprising that many Neo-Confederate groups are connected to the event, since the original stated purpose of the event was to protest the relocation of a memorial statue to Confederate general Robert E. Lee. However, the event also attracted many attendees involved in other extremist ideologies as well.

This data shows that Unite the Right exhibited an alarming ability to attract a broad cross-section of extremists from a diverse set of ideologies. However, despite the event organizer's goal of uniting a perpetually fractured far-right, the violence, arrests, and lawsuits stemming from the Unite the Right event have only served to increase tension and infighting between the groups involved.

ABOUT

Megan Squire is a Professor of Computer Science at Elon University and a Sr. Fellow at the Center for the Analysis of the Radical Right.