Basics of Theory: A Brief, Plain Language, Introduction

By Steve Wallis and Bernadette Wright

Throughout March 2020 we explored research design, with a focus on theory and conceptual frameworks. Bernadette Wright and Steve Wallis, co-authors of Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation, were Mentors-in-Residence in October 2019.

Why worry about theory?

In 1976, (yes, a few decades ago) the band Blue Oyster Cult came out with, “Don’t Fear the Reaper,” a most excellent soundtrack for you to play while you read the rest of this post.

Basically, the song says that death is inevitable, so don’t worry about it. Same with theory. Theory is everywhere, we all use theory all the time every day, usually without thinking about it. So why worry about it?

When we use theories without thinking about them, they arecalled mental models. They are a set of assumptions we’ve built up in our mindsthrough our lives. It’s as if all your life you’ve been doing research in many partsof your life and not even realizing it. Figuring out how the world works so youcan make better decisions to reach your goals.

Although they are often hidden, your mental models willsometimes come to the surface where you can see them. For example, I might findmyself turning off the radio every time a rap song is played because it soundslike noise to me. Then, one day, I actually stop to listen and realize thatthere are some interesting lyrics here! My assumption about rap music guided myactions. Once I looked at my assumptions more clearly, I could change them andso change my actions.

In the academic world, a theory is a kind of model. Sometheories are created from careful research, while others are just confusing pilesof speculation based on various assumptions. Much as you can create and changeyour assumptions, you can create a theory by doing research (you might evenstudy the world of music). And, you can use theory to consciously guide youractions. Those may be small actions such as changing the channel to listen todifferent music or large changes leading to big changes in your community orthe world. The key is that by understanding theory, we can better understandourselves, our world, and what we can do to make our lives better.

So, on one level, a theory is nothing but a printed (or formal)version of someone’s knowledge. It’s just a bunch of text someone wrote toexplain how they think the world works (on any topic… including life, death, love,music, and just getting along with each other). The problem with many theoriesyou’ll read is that they are so poorly explained that they are unhelpful as aguide to research and action. So, let’s focus on the important parts.

Concepts are part of theories

Every theory will have sentences and those sentences willhave concepts. Those concepts are related things in the real world. Forexample, when I write the world “music,” that is a written concept for somethingyou can see (or hear) happening in the real world. Another concept might be “noise”(depending on your tastes and choice of music).

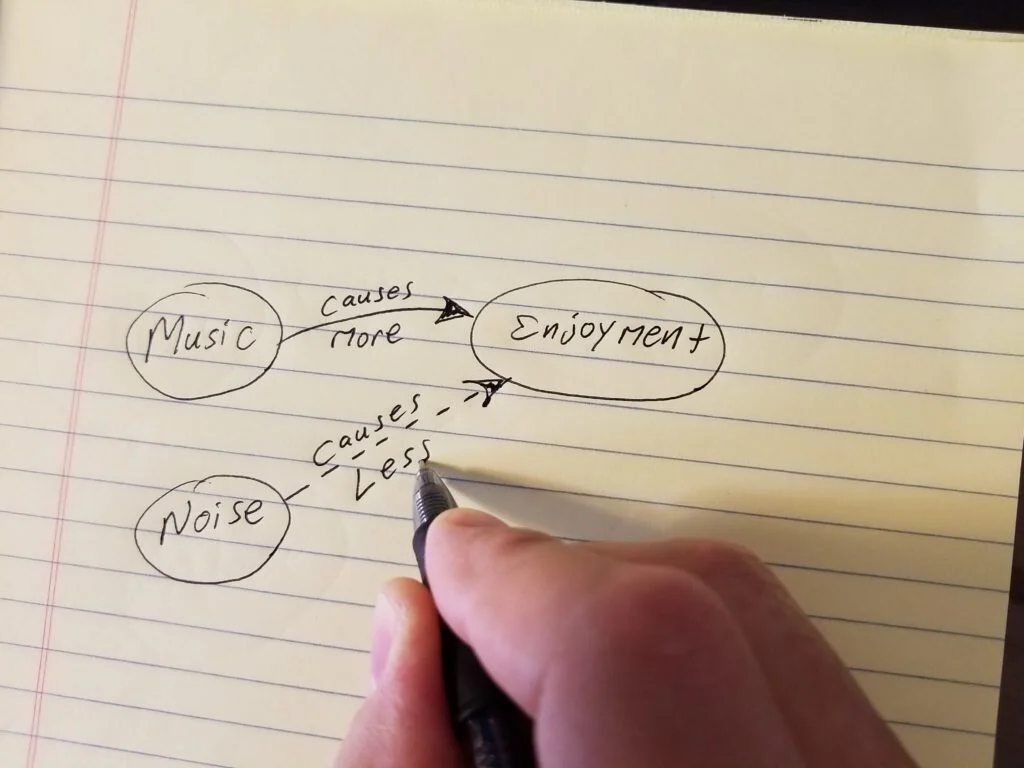

The sentences in a theory will (we hope) also explain therelationships between concepts. The most useful relationships are “causal” relationships.In a causal relationship, the theory talks about one thing causing another (actually,there are usually multiple causes, but let’s keep it simple for now). Forexample, “more music causes more enjoyment” or “more noise leads to lessenjoyment.” Having real world concepts and causal connections are importantbecause that’s how you make things happen. Using this example, you can cause moreenjoyment if you make more music (and/or less noise). The more of the causalconnections pointing to a concept (such as “enjoyment”) you know, the betteryour ability to influence that concept.

By focusing on the concepts and causal connections, you can cut through the confusion and find your way to understand theories more easily. Another handy trick is to draw a diagram of the theory from the text. For example:

This picture serves as a (very simple) practical map showing a theory (based on my assumptions – clearly presented, but not very well researched). Using this map, you can easily see that this theory can be used in any situation where is (or might be) noise, music, and enjoyment.

It should also be clear that you can NOT use this theory forflying a kite, downhill skiing, breeding ferrets, of anything else because those concepts are NOT part of thetheory.

What you CAN do is add to this theory by searching academicjournals and textbooks, or by conducting your own research for things thatcould be connected to noise, music, and enjoyment with causal arrows.

When you cut through all the noise and confusion aroundtheories, there are two main things to look for: measurable concepts andcausal connections. Draw a practical map of those and you are ready torock and roll – you need no longer fear the theory!

For lots more resources on theory building, please visit: https://projectfast.org/resources-for-researchers/

For a good, plain language, text on research and buildingtheories, see: https://practicalmapping.com/

Authors:

Steven E. Wallis, PhD

Director, Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory (FAST)

Capella University, School of Social and Behavioral Sciences

Researching and consulting on policy, theory, and strategic planning

Dr. Wallis is a Fulbright alumnus, international visiting professor, award-wining scholar, and Director of the Foundation for the Advancement of Social Theory; researching and consulting on theory, policy, and strategic planning. An interdisciplinary thinker, his publications cover a range of fields including psychology, ethics, science, management, organizational learning, entrepreneurship, policy, and program evaluation with dozens of publications, hundreds of citations, and a growing list of international co-authors. In addition, he supports doctoral candidates at Capella University in the Harold Abel School of Psychology. Following a career in corrosion control, he earned his PhD at Fielding Graduate University and took early retirement to pursue his passion – leveraging innovative insights on the structure of knowledge to accelerate the advancement of the social/behavioral sciences for improved practices and the betterment of the world.

Dr.Bernadette Wright, Director of Research & Evaluation/Founder

Dr. Bernadette Wright, founded Meaningful Evidence to help nonprofits leverage research to make a bigger impact. She has over two decades of experience designing, managing, and conducting research and evaluation that informs strategies, demonstrates impact, and shapes effective action. With an interdisciplinary background in public policy and evaluation, her research experience has covered aging and disability, health, human services, racial equity/justice, education, and many other topics. Dr. Wright earned her PhD in public policy/program evaluation from the University of Maryland. She is a member of American Evaluation Association and Washington Evaluators.

For more easy tips and in-depth techniques, check out our book: Practical Mapping for Applied Research and Program Evaluation. It uses language that is “99% jargon free” to guide students and experts through every phase of the research/evaluation process, using the practical mapping technique. The book provides unique and effective approaches for developing new knowledge in support of sustainable success for government and non-profits programs working to improve individual lives and whole communities.