Getting Started with Archival Research

What is archival research, and why is it useful for social researchers?

Social researchers in fields such as sociology, business, political science, or education might think that archival methods are the domain of the humanities. But in today's world, we are leaping past such boundaries. Whatever our discipline, we can benefit from the larger context we can gain from using primary sources. While we might think of archives as repositories of materials that can offer historical background, they can also contain more recent resources that can help us gain a better understanding of the research problem or the setting where we plan to study it.

Lewis-Beck et al defined and explained the basics of archival research in theThe SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods:

For the social scientist, archival research can be defined as the locating, evaluating, and systematic interpretation and analysis of sources found in archives.

Many of those sources come in the form of documents. In a SAGE Research Methods Foundations essay, Lindsay Prior (2019) defined documents as:

Document is a word derived from the Latin verb for teaching: docere. A document in that sense is something that functions to explain, instruct, warn, exemplify, substantiate, or prove. [T]he word document tends to be used as a noun—to denote a physical or electronic container of some kind, and what is contained is typically text and related forms of inscription. Thus, letters, diaries, laboratory notebooks, clinical notes, kitchen recipes, transcribed speeches and interviews, reports, notices on posts and doors, graffiti on walls, musical scores, text messages, tweets, and train tickets all qualify as documents along with a myriad of other forms. ... In an age in which communication using images (via, e.g., social media, selfies, and emoticons) can take precedence over communication using text, the notion of what a document “is” has, necessarily, to be broad. Essentially, however, what marks an object as a document is not what it contains nor its physical or electronic format, but its role and use as a conveyor of information.

Documents and other original source materials may be consulted and analyzed for purposes other than those for which they were originally collected—to ask new questions of old data, provide a comparison over time or between geographic areas, verify or challenge existing findings, or draw together evidence from disparate sources to provide a bigger picture.

Archival Research Versus Field Research

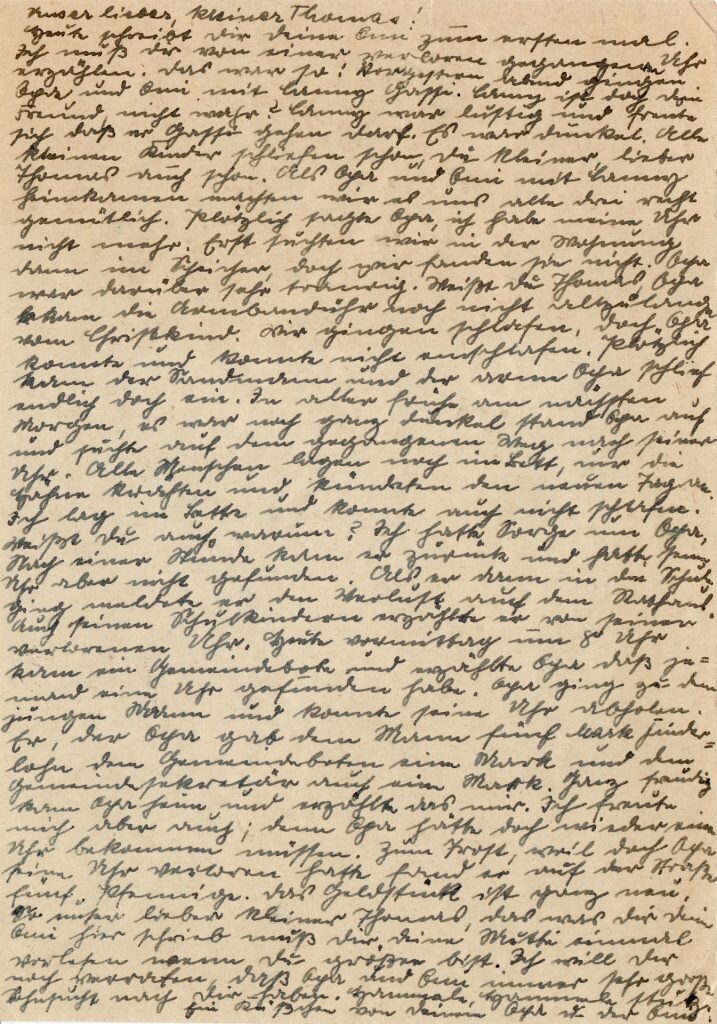

For the social scientist, using archives may seem relatively unexciting compared to undertaking fieldwork, which is seen as fresh, vibrant, and essential for many researchers. Historical research methods and archival techniques may seem unfamiliar; for example, social scientists are not used to working with hand-break written sources that historians routinely consult. However, these methods should be viewed as complementary, not competing, and their advantages should be recognized for addressing certain research questions. Indeed, consulting archival sources enables the social scientist to both enhance and challenge the established methods of defining and collecting data.

What, then, are the types of sources to be found of interest to the social scientist? Archives contain official sources (such as government papers), organizational records, medical records, personal collections, and other contextual materials. Primary research data are also found, such as those created by the investigator during the research process, and include transcripts or tapes of interviews, field notes, personal diaries, observations, unpublished manuscripts, and associated correspondence. Many university repositories or special collections contain rich stocks of these materials. Archives also comprise the cultural and material residues of both institutional and theoretical or intellectual processes, for example, in the development of ideas within a key social science department.

However, archives are necessarily a product of sedimentation over the years—collections may be subject to erosion or fragmentation—by natural (e.g., accidental loss or damage) or manmade causes (e.g., purposive section or organizational disposal policies). Material is therefore subjectively judged to be worthy of preservation by either the depositor or archivist and therefore may not represent the original collection in its entirety. Storage space may also have had a big impact on what was initially acquired or kept from a collection that was offered to an archive.

Techniques for locating archival material are akin to excavation—what you can analyze depends on what you can find. Once located, a researcher is free to immerse himself or herself in the materials—to evaluate, review, and reclassify data; test out prior hypotheses; or discover emerging issues. Evaluating sources to establish their validity and reliability is an essential first step in preparing and analyzing archival data. A number of traditional social science analytic approaches can be used once the data sources are selected and assembled—for example, grounded theory to uncover patterns and themes in the data, biographical methods to document lives and ideas by verifying personal documentary sources, or content analysis to determine the presence of certain words or concepts within text.

Access to archives should not be taken for granted, and the researcher must typically make a prior appointment to consult materials and show proof of status. For some collections, specific approval must be gained in advance via the archivist.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Bryman, A., & Futing Liao, T. (2004). The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412950589

How can I get started?

Kristan Lucas offered practical advice for archival researchers in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods:

Identify a Clear Goal

Archival researchers should begin with a clear research question and a basic idea of what kinds of archival data can be helpful to answering their question. At a minimum, researchers should have a clear topic and time period in mind that will help them target their search efforts. Ideally, the project’s scope should be narrow enough to allow the researcher to explore the full depth of the archival materials.

Make an Initial Inquiry

As a next step, researchers should identify an archive that contains relevant materials or collections. Conducting an Internet search or asking subject matter experts can generate promising direction. Once an archive is identified, researchers should contact the archive directly to make an initial inquiry. As part of the inquiry, researchers should explain their project, indicate the materials they will want to access, and request permission to access materials. Researchers may also ask questions about other relevant materials that may be available, the amount of material in the collection (is it 1 box or 50?), whether any portion of the collection has been digitized, and available technology for recording purposes (e.g., scanners, photocopiers, no technology). The more information researchers are able to gather during the initial inquiry, the better they will be able to plan their visit to the archive.

Participate in an Orientation Interview

Upon arrival at the archive, researchers should participate in an orientation interview with the archivist. The purpose of the orientation interview is for the researcher and archivist to engage in a conversation about the proposed project and its aims. Based on this conversation, the archivist will provide researchers with information about relevant holdings, including related collections that might not be cross-referenced, collections that have yet to be processed, or even collections at other archives.

Learn and Follow the Rules

Archives have developed strict rules to protect the longevity of the materials. Therefore, it is essential that researchers honor all rules. Taking shortcuts or bending rules can seriously limit, and possibly terminate, researchers’ access to archival materials. Each archive will have its own set of rules. However, common rules include forbidding any food or beverages in the archives, forbidding the use of pens, limiting use of phones and cameras, making researchers stow book bags and jackets in a coat room, requiring researchers to wear gloves when touching materials, having a specific way to open folders and turn pages, and only permitting selected materials to be copied.

Search the Collections

There are some relatively standard practices for searching archival collections. First, prior to accessing any materials, researchers usually are required to present an identification card, register with the archive, and agree to comply with the rules. From there, researchers will review finding aids, which are documents that describe the content of particular collections, to determine which boxes from the collection, if any, may be relevant to their search. Researchers will then request specific boxes from an archival staff member, which typically will be delivered one at a time. As researchers work through each file in the box, they should either make copies or identify which items should be copied by a staff member, and take careful notes about the information they are finding. When they have finished their search of one box, they may return that box and request that the next box be delivered.

Archival searching is, by its nature, a slow and deliberative process of combing through a collection piece by piece. Therefore, it is a process of discovery that requires researchers to be patient, attentive, and meticulous. Most importantly, then, researchers should put themselves in a patient mind-set of staying at the archive for as long as needed instead of rushing through the archival search as quickly as possible. However, archival searching often takes much longer than anticipated, especially if researchers are accustomed to precise and immediate computer searches. One strategy to help with being patient is to develop a realistic time estimate for completing an archival search. For example, researchers who intend to review a single year of a daily newspaper for front page stories may estimate it will take 3 minutes per issue to scan the headlines and make a digital copy of pertinent articles. But even at a mere 3 minutes (which would be quite fast), repeating this process for 365 issues would require more than 18 hours of nonstop work.

Next, researchers should be attentive while they are searching. More than simply finding materials to copy and read later, researchers should pay close attention to everything they are viewing so they do not miss any important strands of information. For instance, if researchers were searching for information on a women’s labor strike, they may review a local newspaper for headlines about the strike itself. But if they stay attentive to other clues, they could also glean interesting insights from classified job ads (what other jobs were available to women in the community), letters to the editor (what community members said about the strike), and news stories and images of women (what the dominant gendered expectations were at the time). Also, there may be clues in one part of the collection that can point to other important materials (e.g., names of other key people, organizations, dates, events, publications). To help keep their attention level high, researchers should consider working for shorter, intense bursts of time and taking regular breaks throughout the day.

Finally, researchers must be meticulous in their archival search. At a minimum, researchers should document the exact source location of all materials, including their box and folder numbers. For published articles, researchers should document as much of the citation information as possible (e.g., date, title, publication, page number). Source information will be important when researchers begin to write their results and cite their sources. Also, researchers should check the quality of all copies to ensure lines are not cut off, edges are not blurred, and that the text is readable (e.g., crispness, size). Otherwise, they may end up missing important information or may have to return to the archive to get corrected copies. Finally, researchers should be meticulous in taking notes throughout the search. Researchers will gain important insights from reading the collections as a whole—even though they will be copying only select parts. Archival search notes can capture dominant impressions of findings, provide an opportunity for initial memoing about how the pieces fit together, identify possible leads for additional searches, and keep a log of the search process (which files were accessed, which leads were not helpful). These notes will become invaluable in later stages of analysis.

Take Advantage of Technology

For many years, taking handwritten notes and photocopying were the only options for recording archival documents. New technology has greatly expanded options. For example, researchers can use digital cameras to take high-resolution photographs of images or paper records, digital recorders and voice recognition software to verbally dictate the text of a letter that is not permitted to be copied, and scanners to make text-searchable copies of transcripts. Researchers should request permission from archival staff to use any personal technology in their search.

Give Back to the Archive

When researchers have worked with an archive, it is customary to formally acknowledge the archive (and specific archivists) in resulting publications. Researchers should clearly identify what archives were used for the search, express appreciation in the author’s note, and send a copy of any articles, books, or dissertations to the archive. Additionally, researchers should consider supplementing the collections, if at all possible. For instance, if their search created or uncovered additional information (e.g., oral history interviews, previously undiscovered materials), researchers may consider donating those materials to the archive for preservation. Similarly, if researchers have made digital records of their search, they may consider providing a copy of those electronic files to the archive in order to make the information more accessible to others.

Lucas, K. (2017). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. In M. Allen (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, California. Retrieved from https://methods.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-communication-research-methods. doi:10.4135/9781483381411

Learn about qualitative data analysis approaches for narrative and diary research in these open access articles.