Practical <> Conceptual Questions

MethodSpace explored phases of the research process throughout 2021. In the first quarter we explored design steps, starting with a January focus on research questions. Find the series here.

Finding and Defining the Research Question

In our troubled times, we are surrounded by real problems. Basic assumptions we held even a year ago are in many cases no longer on firm ground, given that the global Covid-19 pandemic has shaken up the ways we live, work, teach, learn, and conduct research. Meanwhile researchers are under increased pressure to demonstrate impact, that is, to show that their findings can in some way make the world a better place. Some already know how to do this, in particular those who take a practical approach such as action researchers and those who conduct evaluations.

In this context, let's think about discerning practical and scholarly research questions. When discussing this process with my doctoral students, I frequently took this book down from my shelf: The Craft of Research (Booth, Colomb, Bizup, Williams, & Fitzgerald, 2016) and referred to Chapters 3. "From Topics to Questions" and 4. "From Questions to a Problem".

The authors observe:

Too many researchers at all levels write as if their task is to answer a

question that interests themselves alone. That’s wrong: to make your

research matter, you must address a problem that others in your community—your readers—also want to solve. (p. 58).

It can be challenging to align the problems we experience or see around us with a scholarly problem that will contribute to the literature. Here is how Booth et al (2016) explain it.

Put in general terms, a practical problem is caused by some condition in the world. ... We solve a practical problem by doing something (or by encouraging others to do something) to eliminate or at least mitigate the condition. But to know what to do, someone first has to understand something better.

That need for knowledge or understanding raises a conceptual problem. In research, a conceptual problem arises when we do not understand

something about the world as well as we would like. We solve a conceptual problem not by doing something to change the world but by answering a question that helps us understand it better. (pp. 58-59)

With these insights and understandings you can do something to change the world. You can also work to make what you've learned available to those working in the field or those experiencing the problem first-hand.

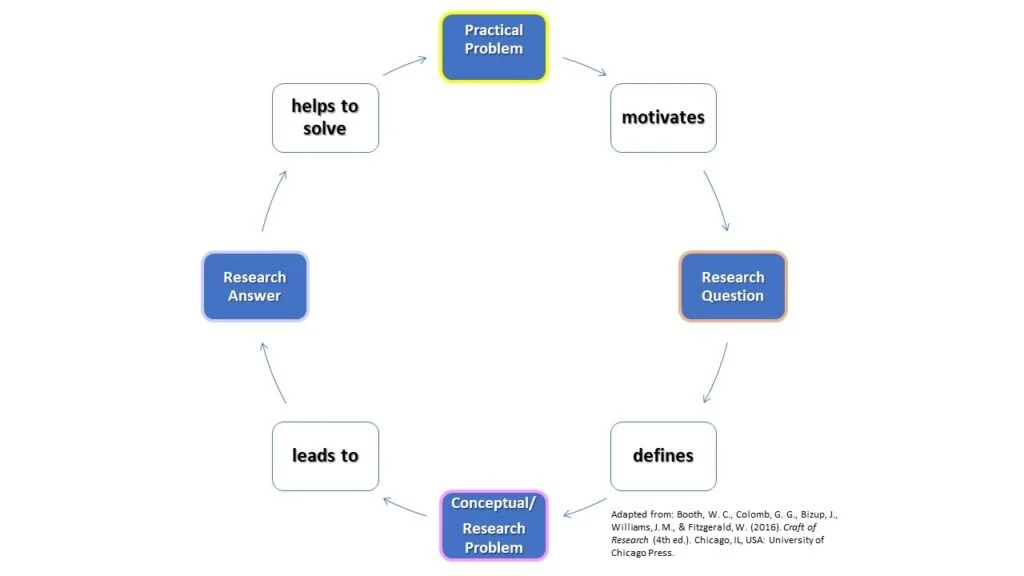

I've adapted the graphic from Booth et al (2016):

By looking at the process as a cycle, we can think through the the sequence that makes sense for our own research.

How can we move forward when a practical problem is the basis for defining the conceptual research problem? Let's start with some first steps needed to define the problem from a scholarly perspective, and articulate your research question(s) :

What evidence can I find about the nature and scope of the problem?Who is experiencing the problem (potential population)?Where are they experiencing the problem (potential setting)? Local, global?How have scholars studied this (or a similar) problem?

Doing some background research will help you clarify the problem, and think about the specific aspects you want to consider. This step encompasses a scan of the literature, but isn't limited by it. Your own experiences, government or other reports or white papers, informal discussions with people close to the problem, can all be helpful when trying to focus and set priorities.

In future posts we will explore other stages of the process-- and more ways to think about defining research problems. Find the unfolding series here.