So What DO I know?: Liberating Inquiry as an Antidote to Doctoral Student Self-Doubt

by Vinay Mallikaarjun with Dr. Sharon M. Ravitch

This post is written by Vinay Mallikaarjun, a first-year doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education and former high school biology teacher. Vinay explores, as a form of liberating self-inquiry, his experience leaving practice, where he was positioned as teacher, to join academia, where he is positioned as learner. Vinay locates this experience in the epistemological hegemony of the Academy, which can have a devaluing effect on students’ wisdom of practice and cultural knowledges. Vinay reflects on the all-too-common student experience of imposter syndrome, offering community thought partnership, mentoring, and co-inquiry as vital to humanization as a scholar-practitioner in academia—his own and those walking the same path elsewhere in the world. This post emerged from conversations with his advisor and mentor, Dr. Sharon Ravitch. Dr. Ravitch was Mentor in Residence for March 2022.

As a first-year doctoral student in my second semester, the last few months have been some of the most rewarding of my life. I’ve been fortunate to engage in robust conversations with insightful professors, challenge my intellectual limits in ways that matter deeply to me, and form close professional and personal bonds with doctoral peers, who have inspired and anchored me as I entered this new realm in the midst of a pandemic.

Becoming a doctoral student, however, is not without its challenges. Some challenges, like the copious amounts of weekly reading and writing done in perpetuity, are expected and necessary hallmarks of the doctoral endeavor. Emergent challenges, such as growing self-doubt and imposter syndrome, are less visible and can manifest in ways that are normalized by the culture of academia and behavior of academics.

As a practitioner returning to the Academy to learn, absorb, and think analytically, I find myself often asking: “What DO I know?” as a liberating self-inquiry.

1) I know that imposter syndrome is real.

When we enter into the Academy, we bring our unique life experiences, interests, capabilities, ideals, strengths, flaws, and much more with us. For me, I bring the unique blend of experiences and perspectives that I have as a former high school science teacher, as a 29-year old man, as a devout Hindu, as an Indian-American, as a semi-professional classical musician, and as the son of two Indian immigrants to the United States. However, the Academy, as a culture, privileges certain experiences and epistemologies while minimizing and devaluing others.

As doctoral students we are placed in a dual positionality of being student and professional. No matter how democratically minded a professor is, students are subordinated within existing power dynamics and hierarchies. We are simultaneously asked to lend our insights and efforts as colleagues towards various professional endeavors, such as working on research projects with professors. In these spheres, we are asked to lay our claim to “knowership” at the door to be assimilated into dominant ideologies of the Academy through our classes and via the research we conduct, even when we arrive with years of practice-based knowledge.

This dual positionality, in combination with the culture of the Academy, often leads to imposter syndrome. In my own experience, imposter syndrome has manifested in a multitude of ways. At the micro level, it is the hesitation to ask a question in a class, speak up in a research meeting, and doubting that our ideas are worthy of intellectual pursuit. At the macro level, it manifests as a pressure to subjugate our identities and positionalities to the ontologies and epistemologies of the Academy, resulting in feelings of de-centeredness and pervasive self-doubt.

2) I know that wisdom of practice matters.

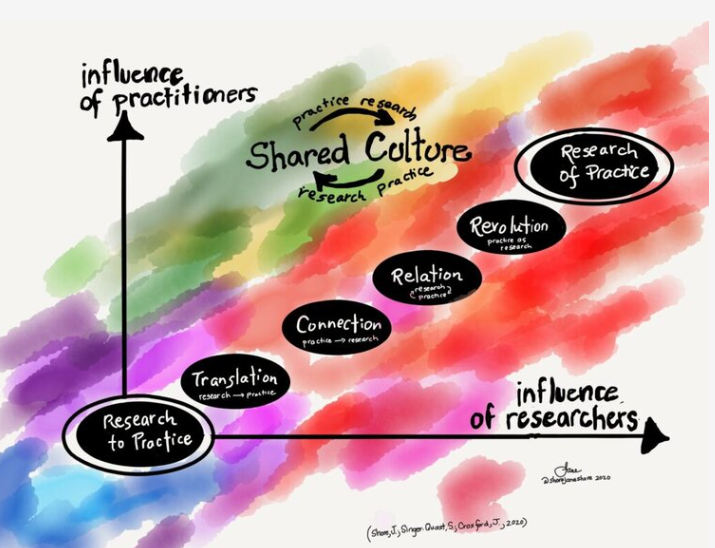

No one enters doctoral study as a blank slate; each of us brings a richness of our experience and, for practitioners, a wisdom of practice. This wisdom of practice, as Shulman (2004) termed it, is an important tool we can use to resist imposter syndrome and make sense of the epistemologies we encounter in academia. My wisdom of practice, grounded largely in the four years I spent teaching high school biology, has been an invaluable lens and resource for navigating doctoral studies. This wisdom of practice allows me to ground the academic knowledge and experiences gained with the insights and skills that I’ve gained from my practice as an educator. The wisdom of practice we bring as doctoral students—as teachers, administrators, organizers, and learners—gives us unique vantage points for assessing the epistemologies presented in our studies rather than accepting them blindly. Wisdom of practice provides ideological agency at a stage in our careers when it can feel that we have little, and so I encourage us to remember the richness of our practice as a site of generative knowledge.

3) I know that doctoral students possess the seeds of game-changing ideas.

The greatest toll my imposter syndrome has taken on me is a conviction that my ideas are not worthy, that they lack validity, utility, or are simply unsuitable for consideration in academia. I know, from conversations with my doctoral peers, that I am not alone in this feeling. When reading the canon of education scholarship, be it the historical writings of Dewey, Vygotsky, and Freire, or the contemporary insights of hooks, Vizenor, and Ladson-Billings, it is natural to wonder about and even doubt how my own ideas can even share the same room as their theories, let alone be placed in meaningful dialogue with them as we are expected to do as budding scholars. In intense moments of self-doubt, it’s tempting to lose sight of what brought me (and I suspect, many of us) to the Academy in the first place: an idea that sparks my passion, that excites me to the core of my being. I know that it is vitally important to reaffirm, first to myself, the importance of my own ideas, research interests, and ways my unique individuality will allow me to contribute meaningful scholarship to the field. By resisting indoctrination that breeds insecurity and affirming the valuable potential of our ideas through liberating inquiry, we can refine our ideas creatively, intellectually, even joyously in community.

4) I know that doctoral students can be greatly aided by mentorship at the intersection of affirmation, intellectual stimulation, and humanization.

Deeply caring mentorship is a compass to navigate the variegated challenges of being a doctoral student including imposter syndrome and all that comes with it. I look for, and am grateful to have, mentorship that recognizes the unique positionality and identities that I bring to my studies, seeking to understand how my unique personhood is best affirmed while reckoning with the challenges of doctoral studies and guiding me to greater growth and success from within myself. If you already have a mentor who inspires you deeply, utilize their support to the fullest extent that you need. If you do not have a mentor yet, I encourage you to actively seek out people who can provide inspirational mentorship for you within your institution.

Imposter syndrome, indoctrination, and self-repression are real, they grow and multiply quietly beneath the surface of seemingly open academic spaces. Antidotes to this include building healthy counter-narratives (to dominant academic ones) that foreground practitioner wisdom and work from the stance that everyone is an expert of their own experience with vital knowledge to share (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). My community of thought partners, mentors, peers, and practitioners deeply inspires me, pushing me to think more deeply each day from a space of affirmation and shared resilience. These brilliant people are pillars of personal growth and professional learning, lighting each other’s way forward. I am happy that at this point in my second semester, I can see that I have valuable knowledge to contribute, and that realization itself is resistance. I am ready to engage in liberating inquiry, fully contributing to, as I gain from, creating new knowledge through community.

References

Ravitch S. M. & Carl, M. N. (2021). Qualitative research: Bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological. (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications.

Shulman, L. S. (2004). The wisdom of practice: Essays on teaching, learning, and learning to teach. Jossey-Bass.

In this guest post Catherine Collins describes ways to put action research principles into practice.