Creating a Culture of Inquiry in the Classroom

by Janet Salmons, Ph.D., Research Community Manager for Methodspace and author of Your Super Quick Guide to Learning Online and Learning to Collaborate, Collaborating to Learn. See this related Methodspace post: Using Inquiry Models to Learn How to Ask Questions.

While Methodsspace is a community of researchers, many of us also find ourselves in the role of teacher or professor. How can we infuse research activities into courses where students learn about methods or curricular courses where they develop critical thinking skills?

The philosopher John Dewey wrote about education in an era with remarkable similarities to our own.

When the telegraph and telephone opened immediate communication across the oceans and continents, Dewey observed that while these technologies had broken down barriers “to bring peoples and classes into closer and more perceptible connection with one another. It remains for the most part to secure the intellectual and emotional significance of this physical annihilation of space” (Dewey, 1916, p. p. 85). At the same time, the nature of work was changing with the Industrial Revolution, and Dewey saw a corresponding need to change the nature of education. He identified a prevalent view, that “the subject-matter of education consists of bodies of information and of skills that have been worked out in the past; therefore, the chief business of the school is to transmit them to the new generation” (Dewey, 1938, p. 17). He criticized it as hopelessly out of step with the need to prepare students for the newly connected world. Instead, he thought students needed opportunities to learn from experience through problem-solving and reflection.

How can we use research activities to build critical skills researchers, professionals, and citizens will need in the future?

So many years later we revisit similar themes. We still grapple with the need to meaningfully, respectfully, bridge distances even though we live in a connected world. Strikingly, today, some welcome globalism and others fear it. We still contend with the educational dilemma Dewey described because simply transmitting information and skills is inadequate preparation for the challenges today’s students will face in academic, professional, and civic life. Technology has made it easier to copy and paste or ask an app or artificial intelligence for an answer, versus thinking critically and creatively. In our time it is ever more important to know how to dig below the surface, discern fact from opinion, use scientific approaches to understand problems, support conclusions with empirically-derived evidence, interpret and apply findings in creative ways. How can we infuse research methods into instructional approaches to develop new habits of mind?

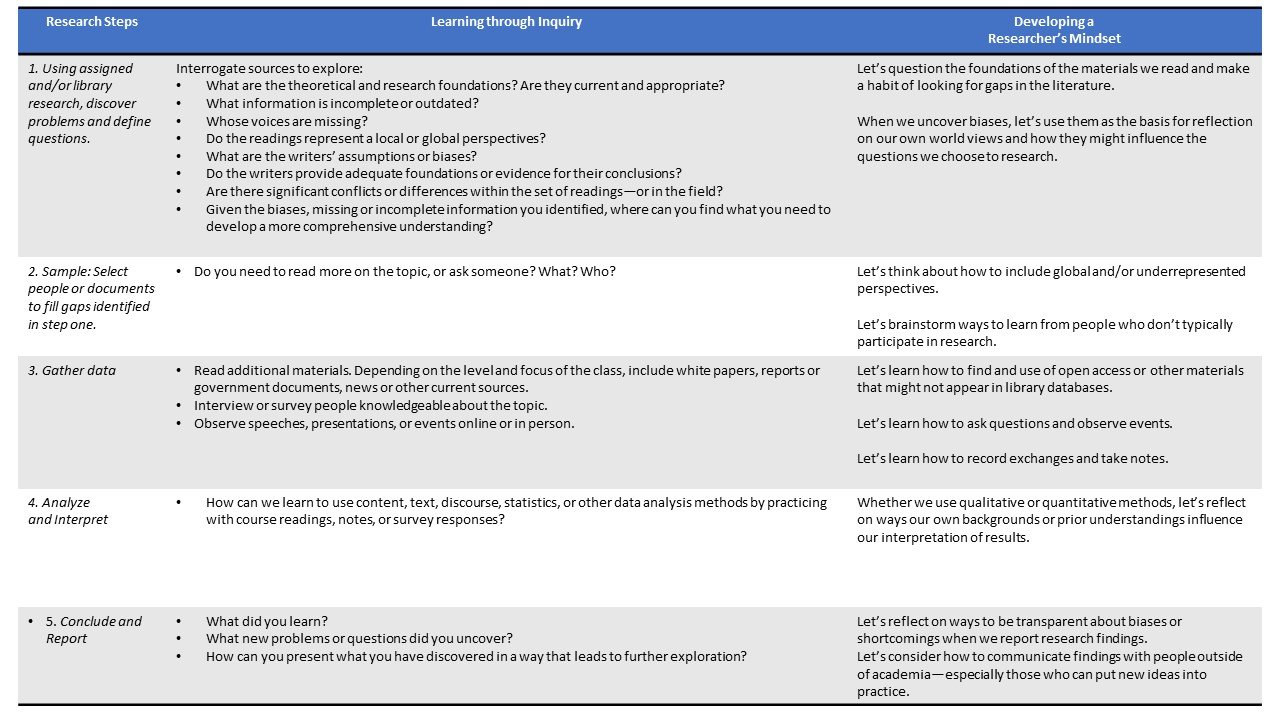

For the moment let’s set aside the details associated with various methodologies and think about the core elements of the research process. In most cases, we begin with a problem, and define the questions we want to answer. We find people or source materials to explore and gather relevant data. After we analyze it, we tried to draw some kind of conclusions then share what was learned by presenting it to others in written or verbal form. We carry out these steps within epistemological and theoretical frameworks that help us understand and explain their positions as researchers in relationships with the world. How can we use these steps to build a culture of inquiry in classes we teach? Here are some suggestions from a learning to research, researching to learn orientation. Depending on the available time and the nature of the class, you can use these ideas to reframe discussions are written assignments, or as the basis for research projects that involve collecting and analyzing data.

Whether we are working with students who are children or adults, by moving from transmission to exploration, we can help our students realize the importance of inquiry. Being prepared to ask hard questions and think critically will be beneficial not only in the classroom or laboratory, but also in their everyday lives. In the process, they will develop mindsets and skillsets that will prepare them to be problem-solvers who are prepared to help us navigate the future in a complicated world.

References

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan Company. Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan Company.

More Methodspace Posts about Teaching and Learning

Listen to this interview, and check out Rhys Jones’ latest book: Statistical Literacy: A Beginner's Guide.

This blog is the seventh, and penultimate post, in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the sixth of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

Latanya Sweeney, scholar of technology science, Daniel Paul Professor of the Practice of Government and Technology at the Harvard Kennedy School and in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and director and founder of the Public Interest Tech Lab, delivered the keynote address for SICSS-Howard/Mathematica 2023.

This blog post is the fifth of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the fourth of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the third of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the second of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the first of eight in a follow-on to our “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby, co-authors of the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters, discuss how to make decisions about what qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods data to collect and how to do so. This post is the third of a three-part series of posts that feature ten author interviews.

Anna CohenMiller helps us drawing on the 4C's of research: Compassion, Community, Care and Collaboration into our research praxis to develop as individuals and researchers.

Doctoral student Sandra Flores discusses her research in Puerto Rico, and what she learned from the experience.

Sage Research Methods Community posts about mentors and mentoring

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby, co-authors of the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters, discuss how to make decisions about methodology in this collection of video interviews. This post is the second of a three-part series of posts that feature ten author interviews.

“Learning about networks, therefore, is to learn key intellectual and empirical skills for navigating through complexity – this descriptor that permeates the world of the 21st century.” Learn more in this guest post from Ion Georgiou.

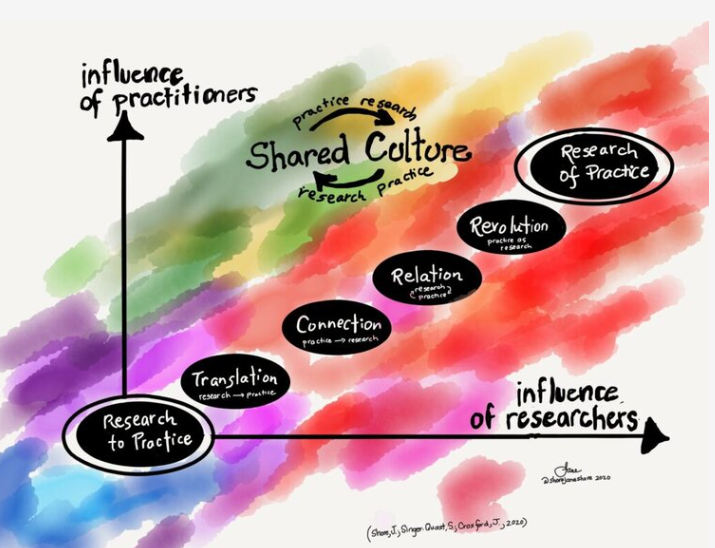

In this guest post Jane Shore and Sarah Singer Quast remind us of the importance of bridging research and practice, and give specific recommendations.

How can you use data science in social science research? Find an interview with the Oxford Internet Institute’s Dr. Bernie Hogan and lots of useful resources in this post.

We need to think about research before we design and conduct it.

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby, co-authors of the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters, discuss the first three chapters in these video interviews:

Chapter 1 – Research Design: What You Need to Think About and Why

Chapter 2 – Ethical Issues in Research Design

Chapter 3 – Developing Your Research Questions

The editor of The Sage Handbook of Online Higher Education, Safary Wa-Mbaleka, is joined by contributors in a lively roundtable about teaching and learning online.

This year we need to honor Martin Luther King's legacy with both reflection and action! In this post, find links to lots of original source materials, including documents and recordings.

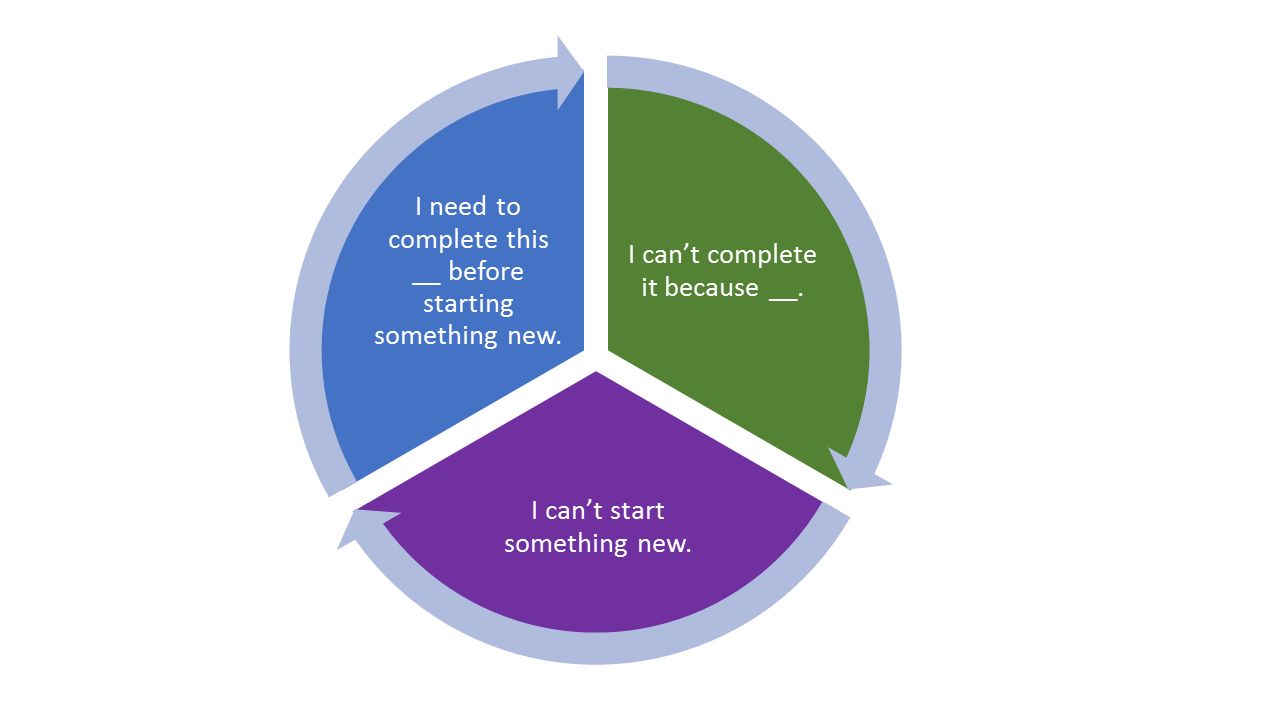

Look candidly at your unfinished project. Is it a stepping stone, and completion will be allow you to move ahead? Or is it an obstacle that prevents you from moving forward? Find ideas to help you determine whether to revive that piece of writing or let it go.

Have a writing project that is languishing? Find practical tips for keeping it alive!

Methods Film Fest!

We can read what they write, but what do researchers say? What are they thinking about, what are they exploring, what insights do they share about methodologies, methods, and approaches? In 2023 Methodspace produced 32 videos, and you can find them all in this post!

How can we teach and learn research methods and academic writing skills using videos? Find 6 ways to use videos with students or to delve more deeply and build your own skills. Make sure to check out Methodspace videos freely available on YouTube.

Many questions were posed by attendees of the Sage webinar, Create a Research Agenda and Personal Academic Brand, with panelists Dr. Mark Carrigan and Dr. Jessica Sowa. Attendees posed many questions. This post is the first in a series - find responses to your questions and links to related resources.

Jessica Lester and Trena Paulus co-edited a December 2023 special issue for the Sage journal, Qualitative Inquiry, “Qualitative inquiry in the 20/20s: Exploring methodological consequences of digital research workflows.” Read the articles and watch a roundtable with contributors. This is the second of two discussions of the special issue.

Jessica Lester and Trena Paulus co-edited a December 2023 special issue for the Sage journal, Qualitative Inquiry, “Qualitative inquiry in the 20/20s: Exploring methodological consequences of digital research workflows.” Read the articles and watch a roundtable with contributors. This is the first of two discussions of the special issue.

Thinking about research careers and calling: finding the right fit.

Use research cases as the basis for individual or team activities that build skills.

Safary Wa-Mbaleka, Arceli Rosario, and Anna Cohen Miller discussed opportunities and challenges for global researchers and academic writers in this roundtable discussion.

This blog post is the eighth, and final, post in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.