Methods in Action: The Ethics of Studying Online Comments

A lot of electronic ink has been spilled on the subject of online commenting on news and social media sites. A lot of that ink has come from academics examining less the content of the comments and more the tenor. But whether looking at the words or the rancor, what would be an ethical way to study comments and to deal with commenters, especially since many of those people have posted anonymously or behind avatars?

Paul J. Reilly, a senior lecturer in social media and digital society at the University of Sheffield, took that question to heart. In an open-access case study featured in SAGE Research Methods Cases, “The ‘Battle of Stokes Croft’ on YouTube: The Development of an Ethical Stance for the Study of Online Comments,” he extends his own research into comments below videos centered on a confrontation over a proposed supermarket outside of Bristol.

For the case study, he detailed his own decision-making on how to ethically use user-generated content for academic purposes. Reilly’s research focuses on online political communication and how social media can promote better community relations in divided societies. His 2011 book, Framing the Troubles Online: Northern Irish Groups and Website Strategy, for example, looks at how the internet could transform the face of conflict in Northern Ireland, and his current research includes a British Academy-funded study of YouTube footage of the union flag protests in Northern Ireland. Reilly has been at Sheffield for a year, and was previously a lecturer in media and communication at the University of Leicester, where he received the Leicester Students’ Union Superstar Award in 2015 based on how he responded to the learning needs of students.

Below, in the latest installment of our Methods in Action series, we asked Reilly about his case study and the broader implications for online research.

What was this individual study about? And what did you find out? The study focused on video footage of the so-called ‘anti-Tesco’ riot in Bristol in May 2011. Media reports linked the violence in the Stokes Croft district of the city to an ongoing campaign by local residents against the decision of Bristol City Council to grant planning permission for a Tesco Express supermarket to be built in the area. Yet, eyewitnesses used online platforms such as Bristol Indymedia to refute these claims, blaming an overzealous policing operation to evict squatters from a building close to the controversial supermarket (which involved the use of police helicopters at one point) for the riot.I was interested in exploring the extent to which members of the Stokes Croft community (and other eyewitnesses) had used social media, in this case YouTube, to record and share ‘sousveillance’ footage that corroborated these allegations. I looked at four of the most commented-upon videos posted on the video-sharing site within 24 hours of the riot, which showed incidents where the police did appear to be heavy-handed (including images of the helicopter that had been the subject of many complaints from local residents). My study examined the themes that emerged from the comments posted in response to these videos. The results indicated that most YouTubers expressed little sympathy for the local residents, with many suggesting that the police should have adopted more aggressive tactics to prevent the anti-social behavior of the rioters caught on camera. There was little rational debate about the causes of the riot, with many comments apparently influenced by the media framing of the riot as a manifestation of the anti-Tesco campaign.

Could you talk a little bit about ‘sousveillance’? Sousveillance (or inverse surveillance) is a concept devised by Steve Mann to explore the empowerment of citizens through technology against the surveillance imposed on them from authority figures. A famous example would be the video footage captured by Los Angeles resident George Holliday in January 1991, which showed several police officers assaulting Rodney King. In recent years, the growth in mobile phone and social media consumption has made it even easier for citizens to capture such footage, whether it be personal (recording their everyday lives) or hierarchical (purposively recording the actions of the police during incidents of civil unrest). It is the viewer who typically determines whether such eyewitness footage constitutes sousveillance or journalism (accidental or citizen).

It seems like drawing from YouTube means your raw data is delivered to your doorstep – but I suspect it’s not quite that simple. What innovative ways did you use to address that? There were three steps required to create the corpus. First, I used a tool (Webometric Analyst) to identify a corpus of 72 YouTube videos tagged with keywords relating to the Stokes Croft riot (I focused on videos posted within four weeks of the riot on the basis that eyewitnesses wishing to hold the police to account for their actions were likely to have uploaded sousveillance footage during this period). The next step was to remove content such as news media reports that did not provide eyewitness perspectives on the policing of the riot. This left a sample of 52 videos, of which I identified the four most commented-upon videos for analysis. Sample characteristics such as the number of views, comments and unique commentators were noted. Finally, two coders read through the comments line-by-line in order to ensure that they conformed to the requirements of the study – namely that they showed some form of engagement with the sousveillance footage under review. This left a total of 1018 text-based comments.

So the case you derive from that original study is less about using YouTube comments to study an event and more about the ethics of doing that. Would you detail the decision-making on whether these comments were to be treated as essentially human subjects, with all the institutional safeguards that suggests, or essentially open text? What decision did you finally come to? In the case I reflect in more detail on the ethical stance that I constructed for this project, especially in relation to the presentation of results. While acknowledging that these videos (and comments) could be considered an ‘open text,’ I decided to anonymize the dataset through the removal of usernames and the paraphrasing of comments. The rationale for this stance was that the verbatim reproduction was not necessary in order to illustrate key themes from the dataset. I also felt that the verbatim reproduction of these comments might inflict reputational harm upon these ‘unaware participants,’ many of whom used offensive language to describe the police.

Is that decision unique to your work, or would you expect to see it applied by all online researchers? This assumes that the key part of your project was on the ‘comments’ as a form of user-generated data, and not just on YouTube as the platform for those comments. In the case, I acknowledge that this was perhaps an ethical stance that other researchers might view as restrictive. Indeed, in subsequent research projects I have reflected more upon whether it is appropriate for scholarly research to automatically protect online participants from negative consequences that might occur from their online behaviors. My own view would be that researchers should assess each specific research context and develop their ethical stance accordingly. They should consider the public benefit of potentially shaming online participants, as well as the most appropriate way to represent themes that emerge from the data. Researchers should be empowered to make informed ethical decisions rather than compelled to follow one-size fits all approaches towards the collection, analysis and presentation of social media data.

Sage Research Methods is a library subscription database. If your academic library subscribes to Sage Research Methods, you can access materials and share them with collaborative partners or your students. If you would like to explore SAGE Research Methods and lack library access, you can use a free trial. SRM contains an extensive collection of books and articles, videos, cases, and datasets.

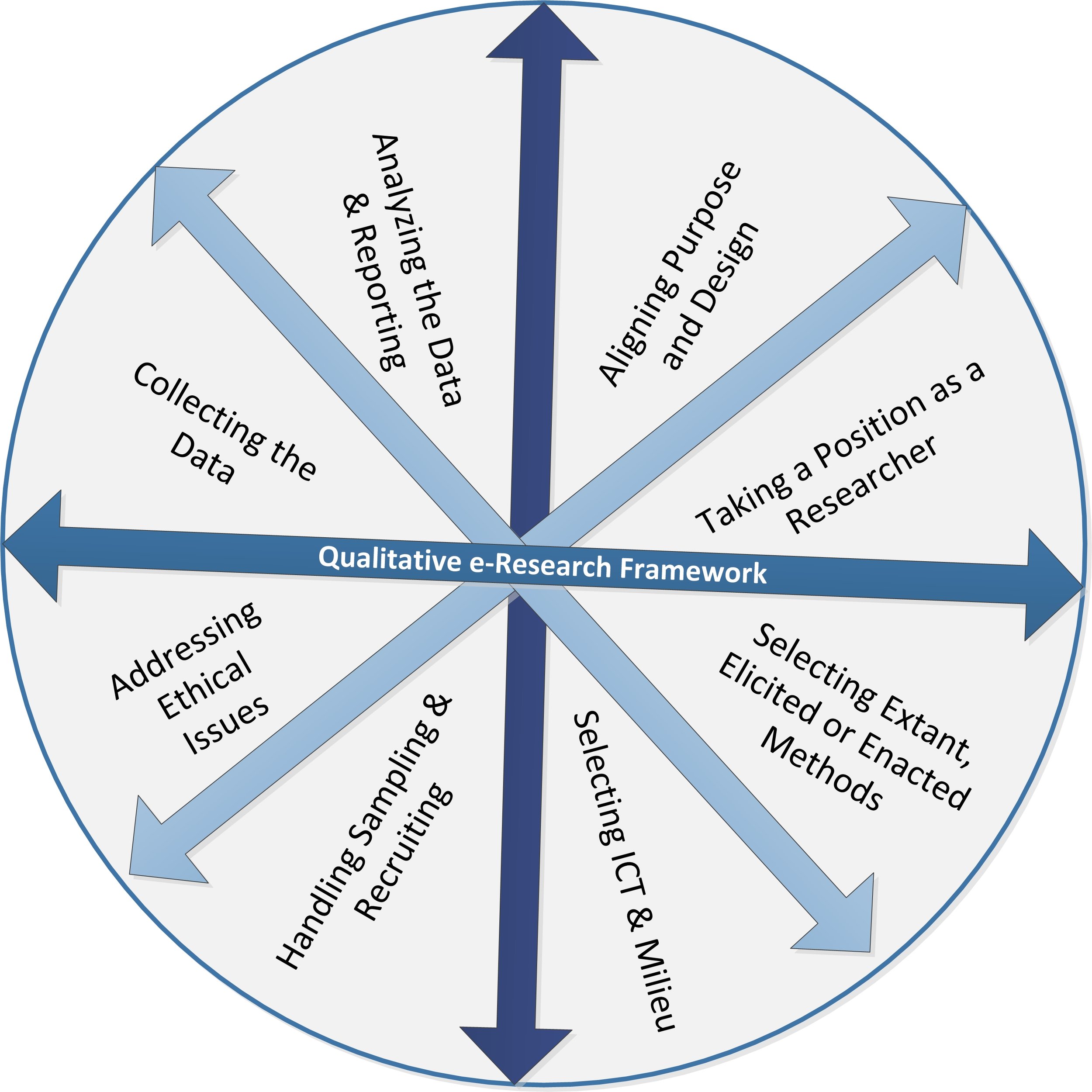

Informed consent is the term given to the agreement between researcher and participant. In this post Janet Salmons offers suggestions about the intersections of the Internet communications, ethics and participants.