Research Ethics in an Ethics-Challenged World

by Janet Salmons, Ph.D. Manager for Sage Research Methods Community

Dr. Salmons is the author of Doing Qualitative Research Online and What Kind of Researcher Are You?. Use the code COMMUNIT24 for 25% off through December 31, 2024

Ethics and scholarly research are inextricably linked.

But it is not always obvious what ethical research means and how we go about ensuring that our studies are conducted and disseminated ethically. Alas, we don't have signposts to follow, in a world where choices for researchers keep evolving. Traditional protocols are not always adequate guidance for dealing with contemporary ethical dilemmas.

For example, if you are an online researcher, you might have cringed to read comments like this one from the New York Times after one of the many Facebook ethical scandals broke a few years ago:

"[Cambridge Analytica] harvested private information from the Facebook profiles of more than 50 million users without their permission. Cambridge paid to acquire the personal information through an outside researcher who, Facebook says, claimed to be collecting it for academic purposes...The data Cambridge collected from profiles, a portion of which was viewed by The Times, included details on users’ identities, friend networks and “likes.” Only a tiny fraction of the users had agreed to release their information to a third party."

Perhaps like me, three particular phrases jumped out in this quote: without their permission, tiny fraction of the users had agreed, and the data were collected based on a claim stating for academic purposes. Clearly, this researcher did not do their homework! Alas, bad behavior reflects on the research community at large. This kind of egregious lapse has a particular impact on qualitative researchers who want to interact with participants, collect their responses to interview questions, or observe their activities in ethical ways. Online research challenges are exacerbated by these kinds of revelations, in addition to other news stories about hacking. Genuine academic researchers increasingly need to build steps into our research process that can overcome suspicions about our purposes and intentions.

To counter suspicions by potential participants, consider the following tips:

Take integrity seriously. You are your first step in ethical research! For many research activities we are alone with our computers, with no one looking over our shoulders. Commit to honesty and transparency. (See related post and interview: What Kind of Researcher Are You?.)

Build your online identity as a credible researcher. You can do an online search to learn more about potential participants or gatekeepers, and they can do the same to learn about you! If they put your name into a search engine, what will they find? New online researchers should create or update profiles and clean up social media accounts. Include links to other publications or relevant accomplishments and link to your institution or other affiliations that will build confidence. If you have an .edu email address, use it.

Don’t forget the “informed” part of informed consent. If we conduct research with participants, we know the importance of informed consent. The agreement process allows us to confirm that our expectations are acceptable to the individuals who will contribute to the study. At the same time, conventional legalese documents are not effective, especially in online research. Avoid overloading participants with extraneous information. Develop concise, clear, jargon-free explanations about your study. Consider a visual form, such as an infographic. Or record a short video or podcast describing the study and explaining privacy protections for the data. Create a simple blog or web page where you can post such information and link to it in social media posts or email signatures. Reiterate this information in multi-stage studies and remind participants of the importance of their participation - and the possibility of renegotiating the agreement if their preferences have changed.

Build relationships in order to access to online groups. Researchers using netnography or other forms of observation often need to negotiate an agreement from a group owner or moderator in order to interact with members and/or access archives. Allow time to develop trust and respect any limits set on data collection. Keep lines of communication open throughout so you can troubleshoot small problems before they become big problems! As relevant, offer to share findings with the group.

Retool your data protection. When I supervised doctoral students, we would chuckle at the guidance that described keeping data in a locked drawer for seven years. Of course one challenge for online researchers is that we sometimes use platforms or programs we don't own. Make an effort to choose platforms and use their features in ways that allow you to download the data onto your own hard drive or flash drive. Password protect files if you share a computer. See Ethics & Interview Platforms.

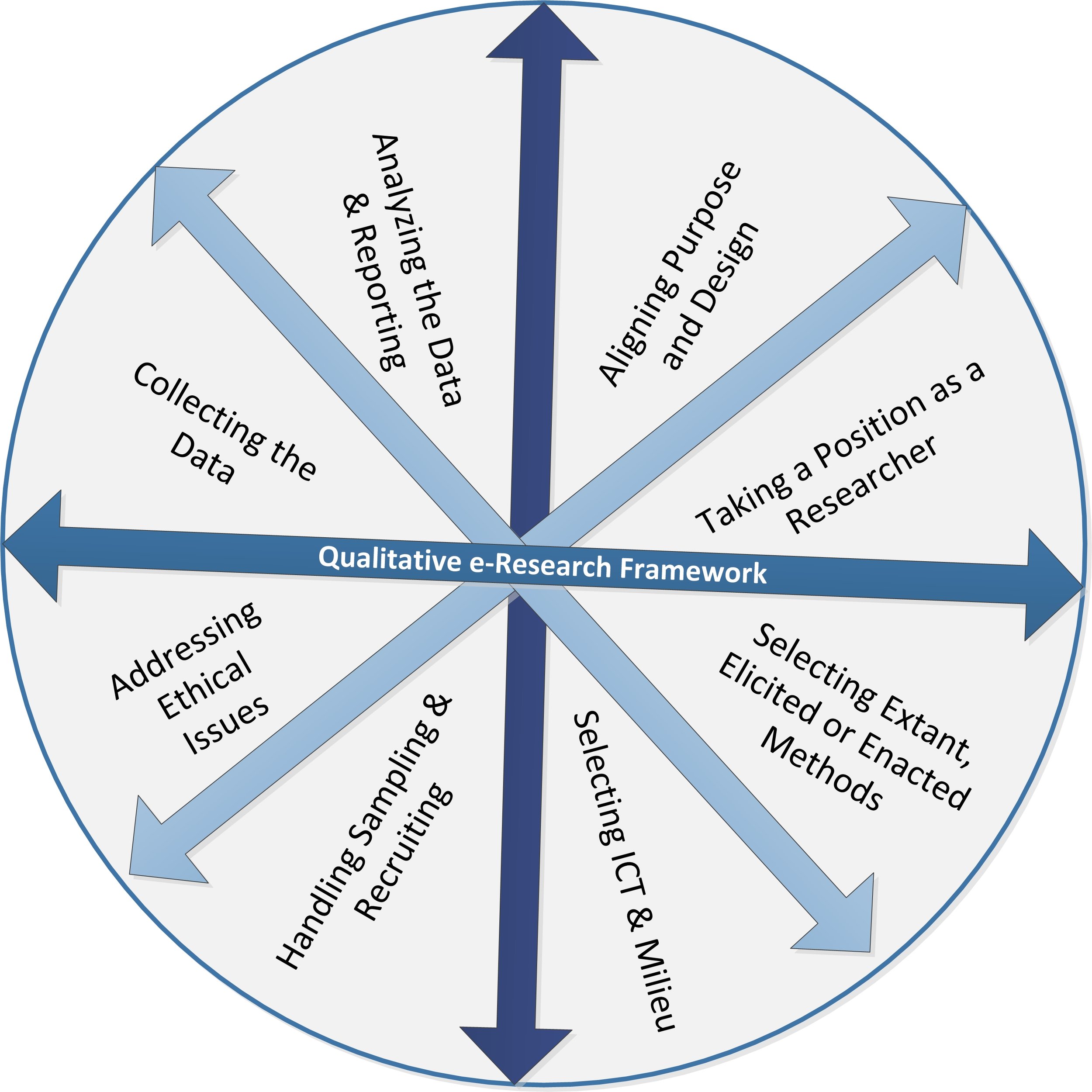

Find more practical guidance about ethical online qualitative research in Doing Qualitative Research Online.

Informed consent is the term given to the agreement between researcher and participant. In this post Janet Salmons offers suggestions about the intersections of the Internet communications, ethics and participants.