Write Reflectively: Reflective Development

by Julian Edwards, author of Write Reflectively.

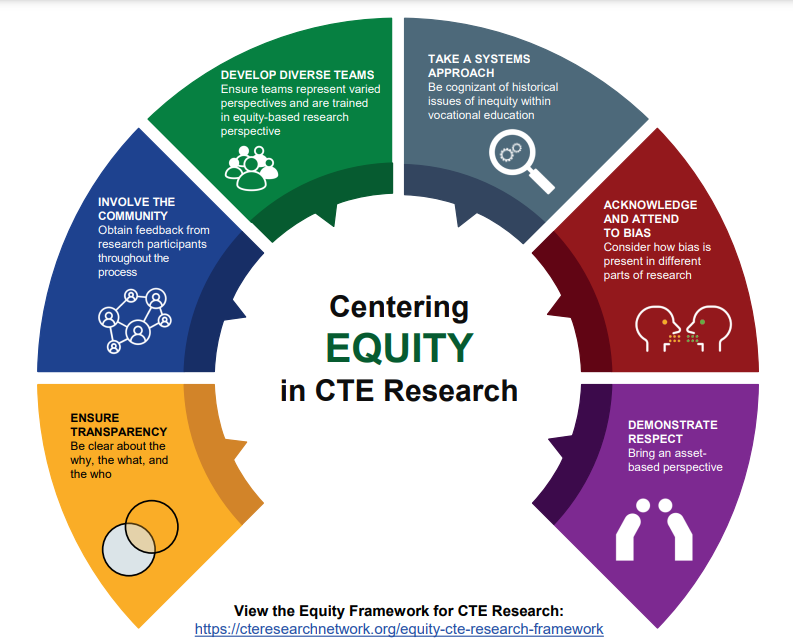

Reflection with others is a key part of understanding how to develop and define ideas from text. Research writing can be developed in regular meetings with others who can help you to define past, present and future goals. A timely and social review of writing can add informed commentary to the initial exploration of broad intuitive ideas. The writer can learn how to use regular reflective practice to define written communication with the input of supervisors, friends, tutors or publishers.

Intuitive discussion on drafts of your writing can generate positive and negative feelings. Both have potential for objective improvement. Self-advocacy can be used to explain motivation which can be tested or justified on the basis of experiential learning. Writing themes can be prioritised using theory and concrete examples to define clarity and meaning.

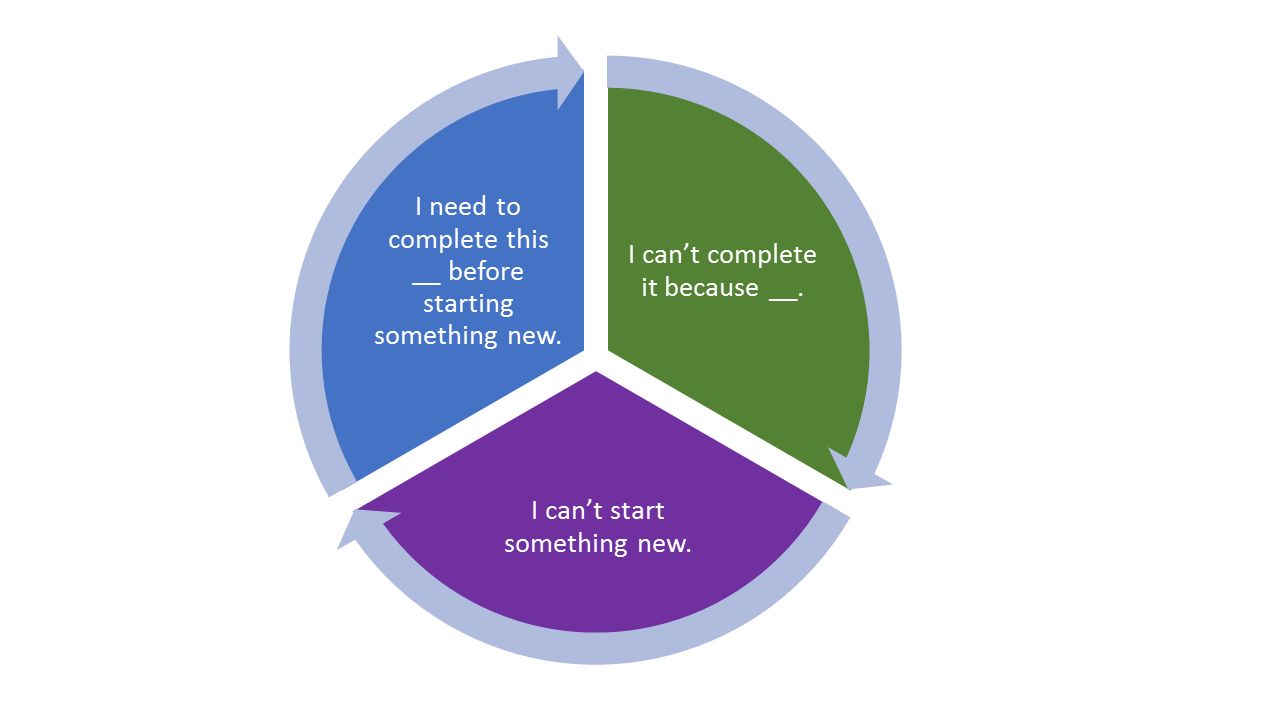

Accepting different points of view can generate breakthroughs in reflective writing research discussion. A choreographed constructive confrontation using the ideas of others may explain the ‘why’ necessary to create an uncomfortable, but necessary change of plan. Regarding the progress from past ideas to the present in a verbalised exploration of differences can overcome personal research impasse. The acceptance of an explanation of differences can improve an understanding of learning development. Past ideas can be revisited as reference points and advanced to and recorded as insight for future research action at regular intervals.

Write Reflectively suggests using a reflective journal as the tool for recording differences of expectation as a basis for action. A social editing space can be used to contrast past, present and future ideas. A template is provided to link feelings to themes, current academic theory and research articles. The writer-researcher can use this journal as a safe testing ground for understanding and recording personal creative development for public discussion or formal assessment.

Write Reflectively suggests personal feelings of regret or failure can be used as motivation. False expectations can lead to false trails and uncertainty, yet ultimately opportunity for a reset and a fresh start. Reflecting with others allows you to stand back from the writing as an impartial observer.

Tasked with reading your writing out loud, a writer can help reduce creative bias and overcome writing blocks. Densely scientific text can be made accessible for the non-expert. This advocacy allows for the acceptance of confusion in meaning, cohesion, grammar or sentence structure when recognised with others in plain sight.

Self-doubt can be the starting point in an explanation breakthrough. Rumination, recrimination and regret can be left behind as the researcher passes milestones in learning how to communicate their skills in reflective writing meetings.

Meetings for social editing can also fathom differences between theory and practice in the research process. Well-intentioned guidelines or accepted routine may need to be adapted to fit your project. The reflective research student can question established academic or professional practice when explaining the ideas behind a problem theme.

The unravelling of a past research anxiety can be knitted into the present by learning how to verbalise concerns about your research writing. This reflective skill to explain and understand learning can be assessed as part of your academic or professional development. Tutors, undergraduates, or professionals can trace personal development over a set period of time, such as a given semester or duration of a research project.

Write Reflectively suggests dialogue as a tool for improved advocacy when editing socially. A light bulb moment may need a social prism to create a full spectrum of possibility. Basic reflective questions can start with: 'What did you intend to write about, what did you finally write about? How did your ideas change as you wrote? When and where did your writing progress best? Why? What would you most like to write about next time? Why?' These questions could bookend regular discussion of research writing where past, present and future writing merges into one thinking space.

This book encourages second chances for the development of fresh action. With the benefit of time, hindsight can produce insight and lead to foresight. The book applies elements of academic writing including analysis, evaluation and critical thinking, to reflective practice. It suggests how students can create regular reference points to review research progress.