New Thinking about Mixed and Multi- Methods

By Janet Salmons, PhD

Mixed and Multi- Methods for this moment

I spend a lot of time talking with researchers. A common theme has emerged over the past year: we need more attention to mixed methods. Researchers using Big Data and large-scale studies need the sensemaking and “what does it mean?” reality check offered by interviews or focus groups. Qualitative researchers who identify trends in small-sample studies need to place findings into a larger context. Perhaps it is hard to address problems in our complex world with one type of data?

Let’s define our terms:

You can mix methods within qualitative and quantitative paradigms, or across paradigms.

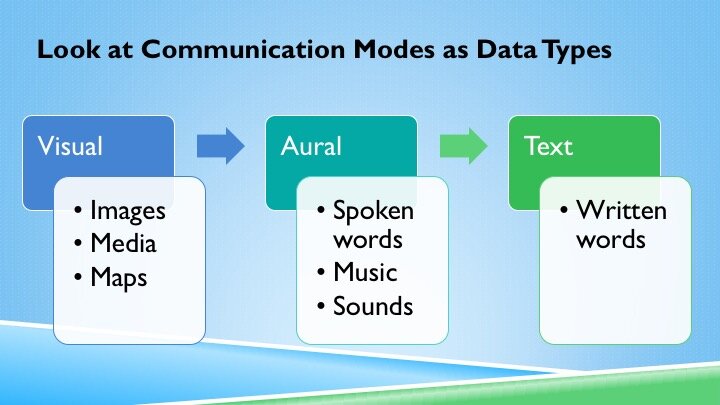

Mixing methods, mixing data

Mixed methods can refer to using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection and/or data analysis methods. Multimethod studies use different styles or types of data collection and/or data analysis methods within the same study. Multimodal studies use different modes of data. For example: if I conduct interviews and use Big Data in the same study it is a mixed methods study. If I use interviews and focus groups it is a qualitative multimethod study, while if I use a survey and Big Data it is a quantitative multimethod study. If I use any of these approaches to collect text data, numerical data, and video data it is a multimodal study. Since these terms might not be defined in precisely the same way across methods literature, it is essential to communicate your choices clearly in your research proposals as well as in the reports generated from the study.

Explaining the mixture

As with any mixture, one part might take priority, or all parts might be used equally. In mixed methods research the term priority refers to the degree of dominance of one method over another. Creswell et al. explain:

The mixed methods researcher can give equal priority to both quantitative and qualitative research, emphasize qualitative more, or emphasize quantitative more. This emphasis may result from practical constraints of data collection, the need to understand one form of data before proceeding to the next, or the audience preference for either quantitative or qualitative research. In most cases, the decision probably rests on the comfort level of the researcher with one approach as opposed to the other. (Creswell et al., 2003)

Using notations helps to succinctly communicate the priorities. The dominant method used is shown with all capital letters: QUAL or QUAN. In a study where both methods are equally important, both are capitalized; if one Is more important, that term is capitalized while the supportive or secondary type of data is shown in lower case: qual or quan (Morse, 1991).

For example, if I am conducting a small number of qualitative interviews to identify issues I want to explore widely in a large-scale quantitative survey, I might describe the interview part as qual, because it is minor stage of the study, and the survey part as QUAN, because it is a more significant part of the research. Or, if the interviews and survey have equal importance, I would indicate that by labeling the stages as QUAL and QUAN.

The second factor is timing. Morgan identified two core assumptions: that in addition to degrees of priority for qualitative or quantitative methods, the designs varied in terms of a sequence of collecting quantitative and qualitative data (Morgan, 2007). Options are:

Concurrent, or simultaneous, meaning both kinds of research are occurring at the same time. This is indicated with a + sign. For example, if I am conducting qualitative interviews while waiting for responses from a quantitative survey, I can describe two types of data collection as concurrent.

Sequential, meaning the researcher collects one kind of data before another. This is indicated with an arrow →. For example, if I am conducting qualitative interviews to identify issues I want to explore widely in a subsequent quantitative survey, I can describe two types of data collection as sequential.

The same principles apply in a multimethod study. In an all-qualitative sequential study I am currently conducting, I am using asynchronous focus groups for the first stage, and synchronous focus groups for the second stage. I will also do concurrent data collection with archival and literature research conducted at the same time as the data collection from human participants. An all-quantitative multimethod study could use analysis of a dataset for the first stage and a survey for the second stage. Or, conduct a survey concurrent with dataset analysis. As with any questions about research design, it is up to you as the researcher to determine what combination of approaches will help you answer the research questions.

Communicate your choices to readers! Notation examples (Salmons, 2015):

QUAL + QUAN Qualitative and quantitative parts of the study have equal weight, and both parts of the study are conducted concurrently, in the same time frame.

QUAL + quan Qualitative and quantitative parts of the study are conducted concurrently. The qualitative part of this study is more significant than the quantitative part.

QUAN + qual Qualitative and quantitative data parts of the study are conducted concurrently. The quantitative part of this study is more significant than the qualitative part.

QUAL → QUAN or QUAN → QUAL Qualitative and quantitative parts of the study have equal weight, but the data was collected sequentially, so one type data is collected before the other.

QUAL → quan Qualitative data are collected before quantitative data. Qualitative data take priority in this study.

QUAN → qual Quantitative data are collected first. The quantitative part of this study is more significant than the qualitative part.

Words are qualitative, numbers are quantitative, right?

Actually, the answer is no. In ancient times when I was an undergraduate at Cornell University’s College of Human Ecology I had a work study job coding a large body of narrative material. Much later I realized what they were asking me to do! We were, in short, translating qualitative data into quantitative data. This process meant that started out as words could be analyzed quantitatively. At the same time, quantitative researchers talk about telling stories with their data. These data scientists offer narrative explanations for relationships between variables, translating statistical information into narratives.

Challenges for researchers who mix methods

Defining and explaining the approach

Fetters, M. D. (2022). A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Research Designs, a Scaffolded Design Figure for Depicting Essential Dimensions, and Recommendations for Achieving Design Naming Conventions in the Field of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(4), 394-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898221131238

Abstract. Since I began my tenure as co-editor in chief of JMMR in 2015, the field of mixed methods research has experienced notable growth in integration, especially of mixed methods procedures combined with other methodologies. Despite this growth, the field has not advanced and remains “stuck” relative to naming conventions of mixed methods designs. That is, what should researchers call designs that combine mixed methods and other methodologies or other essential design dimensions? In this final editorial in my service as co-editor in chief of JMMR, I illustrate this growth in articles that featured combined methodology. I provide examples of how naming of designs has varied among authors, and provide arguments for creating naming conventions. I believe the variation in naming reflects a broader problem of confusion relative to mixed methods design naming and propose a unifying and comprehensive mixed methods design taxonomy based on the Linnaean classification system from the biological sciences. I illustrate how multiple design dimensions could be depicted using a scaffolded design figure. I argue that authors using a primary-secondary methodological ordering in design components could begin moving the field toward greater consistency in naming. I suggest to authors submitting to JMMR an approach for thinking comprehensively about naming of designs and make suggestions for the next steps for the field.

Pedersen, M. A. (2023). Editorial introduction: Towards a machinic anthropology. Big Data & Society, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517231153803

Abstract. Bringing together a motley crew of social scientists and data scientists, the aim of this special theme issue is to explore what an integration or even fusion between anthropology and data science might look like. Going beyond existing work on the complementarity between ‘thick’ qualitative and ‘big’ quantitative data, the ambition is to unsettle and push established disciplinary, methodological and epistemological boundaries by creatively and critically probing various computational methods for augmenting and automatizing the collection, processing and analysis of ethnographic data, and vice versa. Can ethnographic and other qualitative data and methods be integrated with natural language processing tools and other machine-learning techniques, and if so, to what effect? Does the rise of data science allow for the realization of Levi-Strauss’ old dream of a computational structuralism, and even if so, should it? Might one even go as far as saying that computers are now becoming agents of social scientific analysis or even thinking: are we about to witness the birth of distinctly anthropological forms of artificial intelligence? By exploring these questions, the hope is not only to introduce scholars and students to computational anthropological methods, but also to disrupt predominant norms and assumptions among computational social scientists and data science writ large.

Poth, C. N., Molina-Azorin, J. F., & Fetters, M. D. (2022). Virtual Special Issue on “Design of Mixed Methods Research: Past Advancements, Present Conversations, and Future Possibilities”. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(3), 274-280. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898221110375

Abstract. Any discussion of the design of mixed methods research is paradoxically feasible and unwieldy. Feasible because the design of mixed methods research has been widely described in the literature as necessary to initiate prior to beginning research for the purpose of planning research procedures, to continue throughout the research process for the purpose of describing the research logic, as well as to depict the procedures employed after the research is completed for reflecting on threats to validity and research integrity as well as for comparison with other similarly designed studies (e.g., Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Tashakkori et al., 2021). Unwieldy because the design of mixed methods research is so ubiquitous in the literature, it is often difficult to pinpoint exactly what it entails and how these understandings have evolved over time. Its pervasiveness is demonstrated by the more than four hundred “hits” in an article search within the Journal of Mixed Methods Research (JMMR). Our goal in creating this virtual special issue (VSI) is to advance mixed methods researchers’ collective understandings and navigate both the feasible and unwieldy aspects of the design of mixed methods research.

The purpose of this VSI is to engage in imagining a wealth of design possibilities for mixed methods research by drawing upon a curated collection of 10 empirical and methodological articles as well as three editorials previously published in JMMR. We selected articles that we considered to be seminal and as having enduring influence as well as those that were innovative and contributing to contemporary design advancements. We note our attention to include author teams from a range of disciplines, geographical representation, and career stages and that articles included in previous VSIs were excluded. Following our discussions of design advancements and conversations, we conclude with practices that help us to realize our imagined design possibilities.

Younas, A., Durante, A., & Fàbregues, S. (2023). Understanding the Nature of and Identifying and Formulating “Research Problems” in Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898231191441

Abstract. Mixed methods research (MMR) is suitable for studying research problems that cannot be adequately investigated through qualitative and quantitative methods alone. Nevertheless, the MMR literature offers a very limited discussion about “research problems.” To address this gap, this paper uses Elliott’s conceptual framework to offer guidance on how to identify and formulate research problems in MMR and understand their nature. This article contributes to the field of MMR by reframing the concept of research problems in this type of research and offering a conceptual and methodological approach to describing and characterizing research problems for investigation in social and cultural contexts.

Integrating different kinds of data

Fetters, M. D., & Tajima, C. (2022). Joint Displays of Integrated Data Collection in Mixed Methods Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221104564

Abstract. Mixed methods researchers need tools for planning and demonstrating integration. Mixed methods joint displays have a growing presence in the literature for representing mixed methods findings, and for use as an analytic tool as in the case of joint display analysis. However, the joint display of integrated data collection represents a lesser-known application for use by mixed methods researchers. A joint display for integrated data collection links the qualitative and the quantitative data collection questions, scales, and/or items. Here we demonstrate how joint displays of integrated data collection can be used as a planning, implementation, and presentation tool to illustrate integration of the data collection process. We examine variations in joint displays of integrated data collection based on three core mixed methods designs, a convergent design, and two sequential mixed methods designs, and provide examples of each from the literature. We recommend the joint display of integrated mixed data collection as a highly effective tool for mixed methods researchers to use for planning, implementing, and representing integrated data collection in their mixed methods projects.

Younas, A., Fàbregues, S., & Creswell, J. W. (2023). Generating metainferences in mixed methods research: A worked example in convergent mixed methods designs. Methodological Innovations, 16(3), 276-291. https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991231188121

Abstract. Metainferences, or the insights derived from integrating quantitative and qualitative inferences at the end of a study, are crucial for achieving added value and synergy in mixed methods research. There is an ongoing need to understand how researchers generate metainferences, especially considering their pivotal role in helping researchers achieve full quantitative and qualitative integration. While some examples of metainferences generation are available in the mixed methods literature, more explicit guidance is required. Approaches to developing metainferences must also be contextual, as inferences of this type are contingent on the nature and purpose of the mixed methods study, the type of mixed methods design, and the quality of the research data. This paper describes a seven-step process for generating metainferences using a convergent mixed methods study as an exemplar. These steps consist of identifying knowledge, experience, and data-driven inferences from the quantitative and qualitative data; developing inference association maps to draw metainferences; and assessing the validity of metainferences using backward working heuristics. This paper contributes to mixed methods research by shedding light on the development of metainferences in convergent designs and by providing practical and tangible tools for making sense of the complexity of the analysis and interpretation tasks involved in the process of generating metainferences.

Building mixed methods from a qualitative perspective

Poth, C. N., & Shannon-Baker, P. (2022). State of the Methods: Leveraging Design Possibilities of Qualitatively Oriented Mixed Methods Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221115302

Abstract. Mixed methods (MM) research has gained wide global and disciplinary acceptance. However, MM designs that prioritize qualitative perspectives are not easily recognizable yet offer great potential for researchers. By situating the current state of qualitatively oriented mixed methods (QOMM) research and offering practical guidance, we aim to help researchers leverage design possibilities. We begin by positioning ourselves and describing some distinguishing characteristics to help researchers recognize QOMM designs. We then introduce the key features of a QOMM study and weave illustrative examples into the descriptions of six interconnected design spokes to help researchers navigate a nonlinear design process. Finally, we discuss three useful lessons we learned from our own research experiences and consider their implications to help researchers design future QOMM studies.

Fairey, T., Firchow, P., & Dixon, P. (2022). Images and indicators: mixing participatory methods to build inclusive rigour. Action Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503221137851

Abstract. Participatory methods seek to counter the extractive nature of mainstream research methods by putting control into the hands of research subjects. But participation itself does not guarantee against extraction. There is a tension between the desire for researcher-control and the prerogative of community action in participatory methods. How can researchers committed to participation manage this tension? In this paper, we draw on the concepts of “collaborative” and “action-oriented” participatory research to describe how integrating mixed-methodologies can help different research stakeholders attain desirable, fruitful and meaningful levels of ownership and build inclusive rigour. Drawing on our work with participatory indicators and photovoice with conflict affected communities in rural Colombia, we demonstrate how combining different kinds of participatory research methods—in this case, non-visual and visual research—creates opportunities to attend to the sometimes conflicting goals of robust research, policy change and community action. Under the broad umbrella of participatory research, collaborative approaches like participatory indicators and action-oriented approaches like photovoice complement and amplify each other in such settings, embracing complexity and catalyzing multiple ways of ‘knowing-for-action’. The result is participatory research that is attuned to the complexities of conflict-affected settings, inclusively rigorous and potentially transformative.

Gabb, J. (2009). Researching Family Relationships: A Qualitative Mixed Methods Approach. Methodological Innovations Online, 4(2), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/205979910900400204

Abstract. Research has demonstrated how families are constituted through every day practices of care and emotional investment. In this article I suggest that a mixed methods qualitative approach can add another dimension to sociological understandings of these processes. The integration of different qualitative methods produces a dynamic account of everyday family relationships and experiences of intimacy. It shows how the biographical, experiential and social are interwoven, enabling the fabric of family relationships to be unpicked. Drawing on original data from empirical research, I outline the kinds of material produced by different methods and the usefulness of creativity in research design, including innovative methods such as the emotion map and psycho-social approaches to research. Through case study analysis, I demonstrate how the mixing of methods generates multilayered, richly textured information on family relationships but I caution against tidying up all the empirical loose ends. I suggest that there is analytical benefit in retaining some of the ‘messiness' that comprises connected lives.

Building mixed methods from a quantitative or computational perspective

Bjerre-Nielsen, A., & Glavind, K. L. (2022). Ethnographic data in the age of big data: How to compare and combine. Big Data & Society, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211069893

Abstract. Big data enables researchers to closely follow the behavior of large groups of individuals by using high-frequency digital traces. However, these digital traces often lack context, and it is not always clear what is measured. In contrast, data from ethnographic fieldwork follows a limited number of individuals but can provide the context often lacking from big data. Yet, there is an under-explored potential in combining ethnographic data with big data and other digital data sources. This paper presents ways that quantitative research designs can combine big data and ethnographic data and account for the synergies that such combinations can provide. We highlight the differences and similarities between ethnographic data and big data, focusing on the three dimensions: individuals, depth of information, and time. We outline how ethnographic data can validate big data by providing a “ground truth” and complement it by giving a “thick description.” Further, we lay out ways that analysis carried out using big data could benefit from collaboration with ethnographers, and we discuss the potential within the fields of machine learning and causal inference.

Peponakis, M., Kapidakis, S., Doerr, M., & Tountasaki, E. (2024). From Calculations to Reasoning: History, Trends and the Potential of Computational Ethnography and Computational Social Anthropology. Social Science Computer Review, 42(1), 84-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393231167692

Abstract. The domains of computational social anthropology and computational ethnography refer to the computational processing or computational modelling of data for anthropological or ethnographic research. In this context, the article surveys the use of computational methods regarding the production and the representation of knowledge. The ultimate goal of the study is to highlight the significance of modelling ethnographic data and anthropological knowledge by harnessing the potential of the semantic web. The first objective was to review the use of computational methods in anthropological research focusing on the last 25 years, while the second objective was to explore the potential of the semantic web focusing on existing technologies for ontological representation. For these purposes, the study explores the use of computers in anthropology regarding data processing and data modelling for more effective data processing. The survey reveals that there is an ongoing transition from the instrumentalisation of computers as tools for calculations, to the implementation of information science methodologies for analysis, deduction, knowledge representation, and reasoning, as part of the research process in social anthropology. Finally, it is highlighted that the ecosystem of the semantic web does not subserve quantification and metrics but introduces a new conceptualisation for addressing and meeting research questions in anthropology.

Mixing Western, inclusive, and Indigenous approaches

Bentley, C., Muyoya, C., Vannini, S., Oman, S., & Jimenez, A. (2023). Intersectional approaches to data: The importance of an articulation mindset for intersectional data science. Big Data & Society, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517231203667

Abstract. Data's increasing role in society and high profile reproduction of inequalities is in tension with traditional methods of using social data for social justice. Alongside this, ‘intersectionality’ has increased in prominence as a critical social theory and praxis to address inequalities. Yet, there is not a comprehensive review of how intersectionality is operationalized in research data practice. In this study, we examined how intersectionality researchers across a range of disciplines conduct intersectional analysis as a means of unpacking how intersectional praxis may advance an intersectional data science agenda. To explore how intersectionality researchers collect and analyze data, we conducted a critical discourse analysis approach in a review of 172 articles that stated using an intersectional approach in some way. We contemplated whether and how Collins’ three frames of relationality were evident in their approach. We found an over-reliance on the additive thinking frame in quantitative research, which poses limits on the potential for this research to address structural inequality. We suggest ways in which intersectional data science could adopt an articulation mindset to improve on this tendency.

Clarke, G. S., Douglas, E. B., House, M. J., Hudgins, K. E. G., Campos, S., & Vaughn, E. E. (2022). Empowering Indigenous Communities Through a Participatory, Culturally Responsive Evaluation of a Federal Program for Older Americans. American Journal of Evaluation, 43(4), 484-503. https://doi.org/10.1177/10982140211030557

Abstract. This article describes our experience of conducting a 5-year, culturally responsive evaluation of a federal program with Indigenous communities. It describes how we adapted tenets from “participatory evaluation models” to ensure cultural relevance and empowerment. We provide recommendations for evaluators engaged in similar efforts. The evaluation included stakeholder engagement through a Steering Committee and an Evaluation Working Group in designing and implementing the evaluation. That engagement facilitated attention to Indigenous cultural values in developing a program logic model and medicine wheel and in gathering local perspectives through storytelling to facilitate understanding of community traditions. Our ongoing assessment of program grantees’ needs shaped our approach to evaluation capacity building and development of a diverse array of experiential learning opportunities and user-friendly tools and resources. We present practical strategies from lessons learned during the evaluation design and implementation phases of our project that might be useful for other evaluators.

Harriden, K. (2023). Working with Indigenous science(s) frameworks and methods: Challenging the ontological hegemony of ‘western’ science and the axiological biases of its practitioners. Methodological Innovations, 16(2), 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991231179394

Abstract. Globally, Indigenous scientific frameworks and methods have been damaged and derided by ‘western’ science, a strategy of the colonial project. Contemporary Australia is no exception, with the transmission of the suite of scientific values and practices formed over millennia in and for this place being actively prevented by legislation, government policies and colonial opprobrium. This paper shows how two crucial Indigenous science(s) frameworks, used alongside two Indigenous research methods, can transform hegemonic scientific research and fieldwork priorities and practices. This transformation occurs because of the focus of each framework. The first, centring country, requires decentring the human to bring forth the needs of the web of relationships that is country. The second framework, relational accountability, is about tending to a broad range of relationships, are often kin-based and including the other-than-human, with yindyamarra (or local equivalent). Relational accountability also offers an inbuilt ethic of care superior to institutional ethics protocols. By describing these frameworks and methods and discussing how and when to use them, this paper supports their greater understanding and more widespread use, particularly by Indigenous practitioners, so we may continue to (re)build what colonisation has damaged.

Martel, R., Shepherd, M., & Goodyear-Smith, F. (2022). He awa whiria—A “Braided River”: An Indigenous Māori Approach to Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(1), 17-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689820984028

Abstract. While literature on mixed methodology predominantly focuses on North American and European philosophical stances, non-Eurocentric worldviews and indigenous philosophies are also relevant to mixed methods research. This article aims to present the indigenous Māori worldview (te ao Māori) and how this lends itself to mixed methods research, in a New Zealand European and Māori partnership, to conduct bicultural research. The authors use the Māori metaphor He awa whiria (braided river) to describe combining the strengths of two distinct worldviews into a “workable whole.” A framework brings together these two different paradigms as equals, incorporating both numerical and opinion-driven results. The authors illustrate this with a research example of creating a bicultural research framework, underpinned by mixed methods research philosophy.

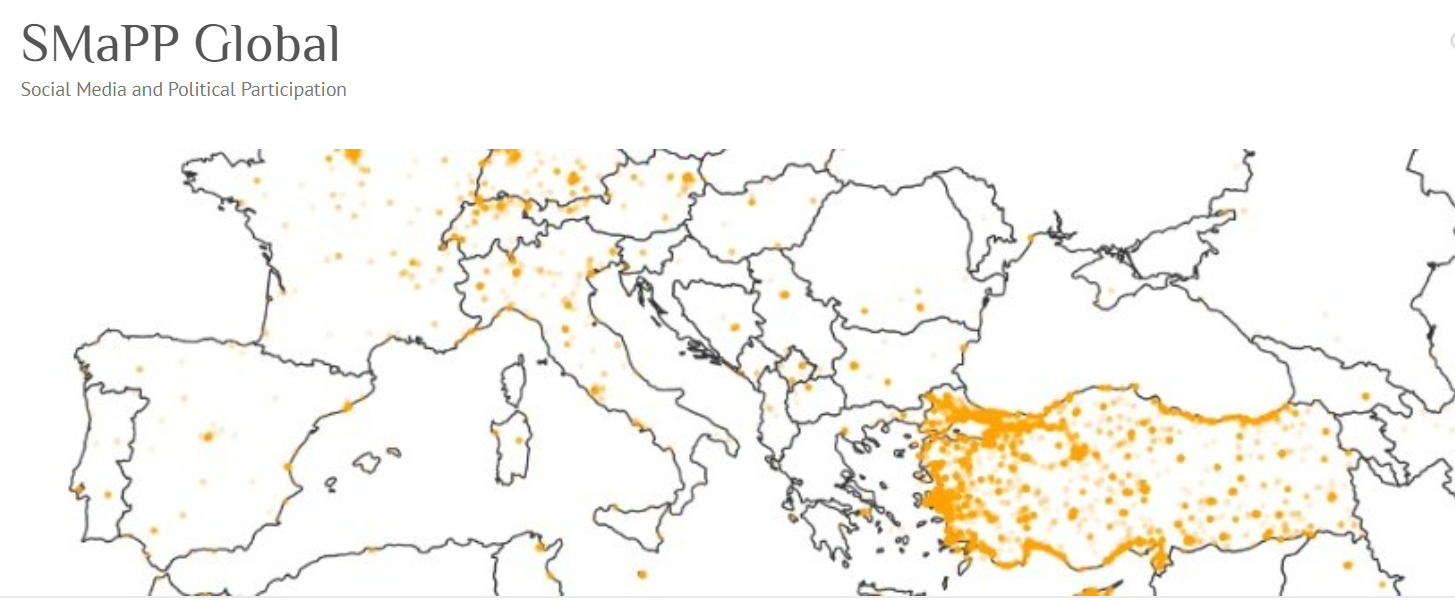

Nikunen, K. (2021). Ghosts of white methods? The challenges of Big Data research in exploring racism in digital context. Big Data & Society, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211048964

Abstract. The paper explores the potential and limitations of big data for researching racism on social media. Informed by critical data studies and critical race studies, the paper discusses challenges of doing big data research and the problems of the so called ‘white method’. The paper introduces the following three types of approach, each with a different epistemological basis for researching racism in digital context: 1) using big data analytics to point out the dominant power relations and the dynamics of racist discourse, 2) complementing big data with qualitative research and 3) revealing new logics of racism in datafied context. The paper contributes to critical data and critical race studies by enhancing the understanding of the possibilities and limitations of big data research. This study also highlights the importance of contextualisation and mixed methods for achieving a more nuanced comprehension of racism and discrimination on social media and in large datasets.

References

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V., Gutmann, M. L., & Hanson, W. E. (2003). An expanded typology for classifying mixed methods research into designs. A. Tashakkori y C. Teddlie, Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research, 209-240.

Morgan, D. L. (2007). Combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 48-76.

Morse, J. M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nursing Research, 40, 120-123.

Salmons, J. (2015). Conducting mixed and multi-method research online. In S.-H. Biber & B. Johnson (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Mixed and Multimethod Research. Oxford Press.

Learn what to do when you are faced with next steps after coding qualitative data.