Part Two: Equity Approaches in Quantitative Analysis

by Lois Joy, Ph.D., Research Director for Jobs for the Future, and member of the CTE Research Network Equity Working Group.

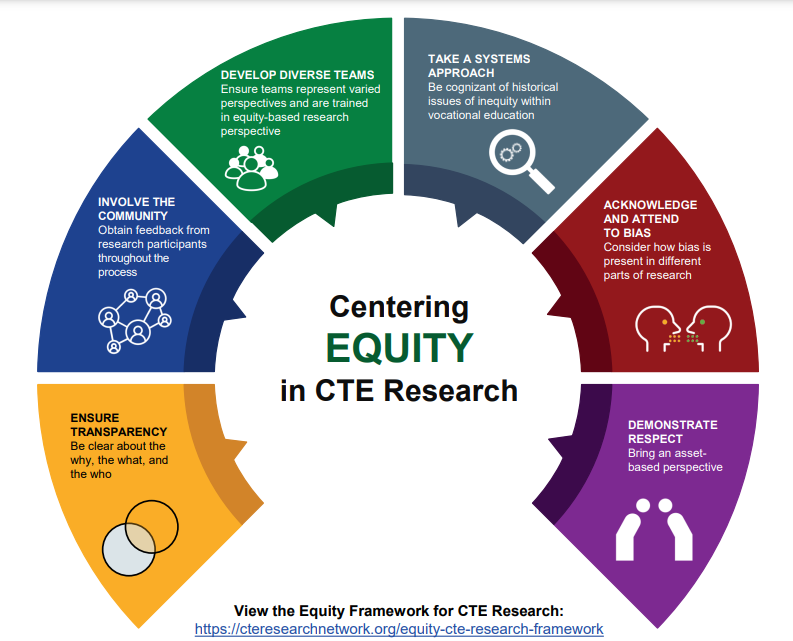

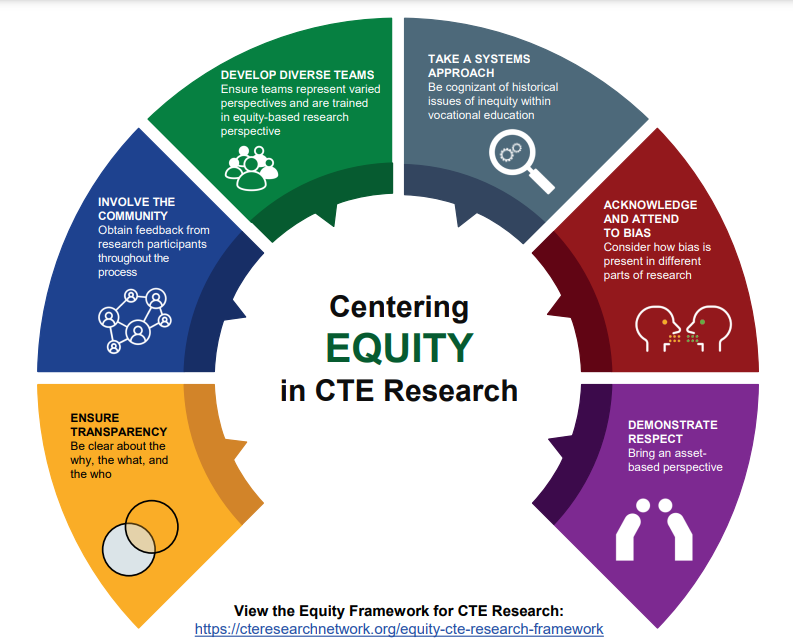

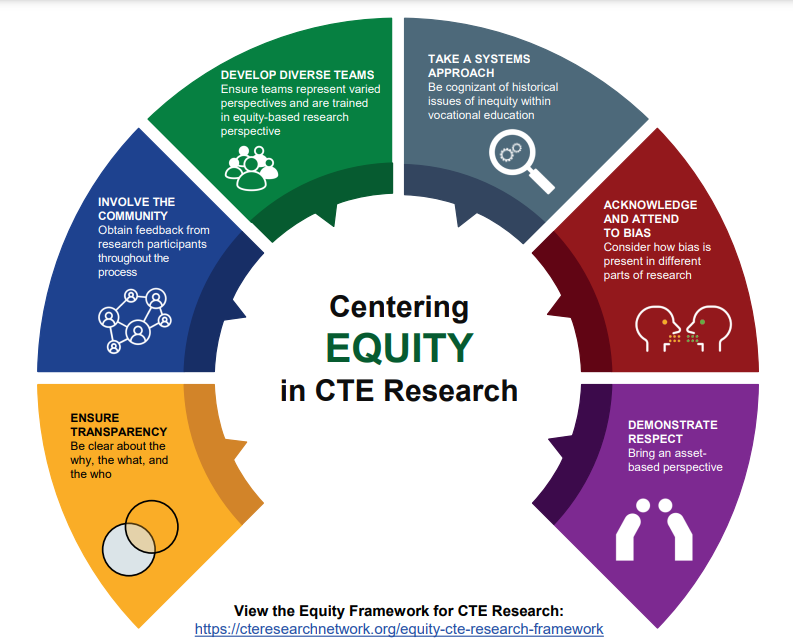

To support equity in CTE research, the Equity Working Group from the Career and Technical Education Research Network (CTERN) authored an Equity Framework for CTE Research which provides principles and practices for researchers on equity questions, designs, and implications throughout the research process. While this guide was authored with a specific focus on Career and Technical Education (CTE) research, the ideas within represent the expertise of a variety of experts in education research. Researchers from all social sciences could implement most if not all the recommendations. This is part two of a two-part blog that focuses equity on quantitative data analysis. Part one calls for equity approaches in quantitative data analysis and part two focuses on analytic practices that support these approaches.

Learn more about using the Equity Framework in your research!

In the CTE Equity Framework, we explore how researchers can integrate equity approaches in creating datasets, structuring analysis, estimating multivariate data, and interpreting findings in ways that highlight systems of oppression that many people navigate in social, educational and workforce settings. The main issues to be addressed in this blog: 1) how to effectively code for race/ethnicity, genders, and disability given limitations in how the data were collected and sample sizes; 2) how to set up appropriate comparison groups for identifying the effects of racism, sexism, ableism and other forms of identity-based oppression, 3) how to control for the way groups are selected into different programs or policies, including which options are feasibly available; and 4) interpretation of findings.

In terms of coding the data, the main equity consideration is how to make various groups visible given the limitations of how the data were collected and small sample sizes. One of several examples from the framework asks, should someone who chooses Black and Latine be placed into the same group as someone who chooses white and Latine? It would be preferable to create two different groups to capture the “intersectional” reality of people’s race/ethnicity and other identities. However, small sample sizes might pose a challenge to not only analysis but also to the protection of confidentiality. When fine-grained groupings are not possible, an alternative option would be to run estimations using different kinds of race/ethnicity groupings to test the robustness of findings on these variations.

In setting up comparison groups to assess outcome gaps, if we only use the dominant group for comparison - in the analysis and visualizations - without taking into inequities in access to resources, support, culturally relevant approaches to CTE pathways, it can make it seem as if the group of interest is deficient in individual capabilities for success. To make more visible how racism, sexism, and ableism and other systemic barriers interact to impact group outcomes, researchers can conduct and compare between and within-group coefficients of key participation and outcome variables. For example, in a regression of the determinants of CTE program participation, the coefficients on the race/ethnicity variables in a sample pooled by race will measure between group differences in participation with the control or structural variables held constant across all race/ethnic groups. In contrast, unpooled participation regressions will allow coefficients on key variables to vary by race/ethnicity allowing researchers to explore, for example, how different factors like proximity to schools offering programs impacts racial/ethnic gaps in participation. These within-group comparisons especially can allow for an exploration of the intersectionality of multiple group-identities on outcomes which research has shown is not linear but complex.5 We can also see how much of the variation in the outcome variables is explained by the independent variables by race and ethnicity.

With counterfactuals, we are asking what would the environment and outcomes look like without the intervention? To address equity concerns, researchers need to document whether and how the counterfactual conditions might vary by group (e.g., by genders or by race/ethnicity). Because of gendered and racialized differences in how people are treated in schools and labor markets (and their resources), the experiences of different groups of people in the nontreatment group may vary; they cannot be presumed to be the same when setting up the counterfactual.

Sample selection is a major issue in program and intervention evaluations and research. To understand how and why persistence and outcomes vary, we need to know how learners and workers are selected into programs, schools, occupations, for example, along with how viable choice sets vary by groups because of sexism, racism, and ableism. From an equity lens, complications include the possibility that not only individual factors but also sexism, racism, and ableism may constrict selection. For example, because biased stereotypes and institutional practices can reinforce occupational segregation by gender, people of various genders may face very different feasible choice sets in the selection of fields of study. Women and nonbinary people may not feel that advanced manufacturing is welcoming. Strategies to address group-related selection bias in analysis could include estimating a group selection effect and an individual effect of participation.

A key consideration for the interpretation of findings is what the genders, race/ethnicity, or other demographic variables are measuring. In most cases, it will be a combination of macro/social, meso/organizational, and micro/(individual and interpersonal) factors that drive group differences in participation and outcomes. The magnitude of and variance in unobservables will vary by group. As we noted above, this idea, as developed in critical race, intersectionality, Black feminist and feminist economic theory, is that the group is not only an individual identity but also a social process, a social location, and a dependent variable. To the extent possible, researchers should consider how group-level gaps in education or workforce participation and outcomes are shaped by the systemic and institutional practices and policies that re-create marginality. Qualitative inquiry can help shed light on the interpretation of findings, especially when studying how the implementation of programs, policies, and strategies might differentially impact outcomes by groups.

The aim of our critical approach to quantitative analysis is to help us overcome blind spots in our analysis that perpetuate rather than elucidate and ameliorate structural barriers to the positive outcomes we are studying.

This is the sixth in an eight-part blog series on the Equity Framework for Career and Technical Education Research authored collaboratively by the CTE Research Network’s Equity Working Group and previously published by the American Institutes for Research.

More Methodspace Posts about the Equity and Research

While progress has been made, social and systemic biases continue to produce inequities in scholarly reference lists, citational indexes, and even journal metrics. This guidance outlines steps that researchers can take toward achieving more inclusive and equitable scholarly citational practice.

This blog is the seventh, and penultimate post, in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the sixth of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

Latanya Sweeney, scholar of technology science, Daniel Paul Professor of the Practice of Government and Technology at the Harvard Kennedy School and in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and director and founder of the Public Interest Tech Lab, delivered the keynote address for SICSS-Howard/Mathematica 2023.

This blog post is the fifth of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the fourth of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the third of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the second of eight in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

This blog post is the first of eight in a follow-on to our “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.

Applying an equity focused lens specifically to reporting and dissemination necessitates a careful and deliberate approach. Learn more in this post!

Learn about disseminating research with an equity lens in this guest post from the CTE Research Network Equity Working Group.

Given the difficulties that emerged with the global Covid pandemic, the European Commission funded the PREPARED project. The aim of the project is to develop an ethics and integrity framework to guide researchers working to prevent and address large-scale crises. Find meeting reports, recordings, and related posts.

The Career and Technical Education (CTE) Equity Framework approach draws high-level insights from this body of work to inform equity in data analysis that can apply to groups of people who may face systemic barriers to CTE participation. Learn more in this two-part post!

The Career and Technical Education (CTE) Equity Framework approach draws high-level insights from this body of work to inform equity in data analysis that can apply to groups of people who may face systemic barriers to CTE participation. This is part 2, find the link to part 1 and previous posts about the Equity Framework.

Some of us feel that technology is everywhere, but that is not the case for everyone. Inequalities persist. What do these disparities mean for researchers?

Why does identity matter in the methods classroom?

How to look at data collection using an Equity Framework for CTE Research, which provides principles and practices for researchers on equity questions, designs, and implications throughout the research process.

Find a multidisciplinary collection of scholarly and historical articles about Juneteenth.

The opening plenary of SICSS-Howard/Mathematica 2022 featured a fireside chat with Dr. Anthony K. Wutoh, the Provost of Howard University, and Dr. Amy Yeboah Quarkume, an Associate Professor of Africana Studies, to kick off the event.

The first Summer Institute in Computational Social Science held at a Historically Black College or University, returns to Howard University for its two-day pre-institute, Praxis to Power for graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, and beginning faculty who needed more time to practice computational methods.

For researchers interested in incorporating equity into their work, it all starts at the very beginning with designing the study. Learn more in this guest post!

The Equity Working Group of the CTE Research Network (CTERN) has published a new framework for any researcher in social or education fields on using an equity lens to do their research. Find a link to The Equity Framework for CTE Research and information about a free webinar.

Summer Institute in Computational Social Science site sponsored by Howard University and Mathematica (SICSS-Howard/Mathematica) awards individuals and teams for the inaugural Excellence in Computational Social Science Research Fund as a unique and exclusive benefit offered to alumni of the site.

A SICSS-Howard Mathematica 2021 participant shares how he reconnected with others in a meaningful way and grew personally during his virtual SICSS experience.

Paul Decker PhD, president and chief executive officer of Mathematica and nationally recognized expert on policy research, delivered the closing plenary address on Friday, June 25th at SICSS-Howard/Mathematica 2021.

Timnit Gebru, co-founder of Black in AI, advocate for diversity in the field of technology, and Fortune’s Top 50 Leaders in the World in 2021 delivered the keynote address for SICSS-Howard/Mathematica 2021.

The first Summer Institute in Computational Social Science hosted at a Historically Black College or University featured a panel of guest speakers who inspired participants with their research and professional trajectory. Lecture topics include re-entry into the job force for incarcerated people, financial statuses of small businesses in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, social identities and systems of power, and discriminatory bias within technology.

SICSS-Howard/Mathematica participants had the benefit of novel Bite-Sized Lunchtime Talks during the inaugural SICSS at a Historically Black College or University. The purpose of this SICSS-H/M specific site innovation was to introduce participants to people and organizations doing impactful and complementary work with data.

Wayne A.I. Frederick, seventeenth president of Howard University, delivered the opening plenary address on Sunday, June 13th at the end of SICSS-Howard/Mathematica 2021’s pre-institute, Praxis to Power.

This blog post is the eighth, and final, post in a follow-on to our 2021 “The future of computational social science is Black” series, about a Summer Institute in Computational Social Science organized by Howard University and Mathematica. It continues to bring the power of computational social science to the issues of systemic racism and inequality in America. This marks the third iteration of the successful SICSS model being hosted by a Historically Black College or University.