Using an Equity Lens in Measurement and Data Collection

by Samuel J. Kamin, Ph.D. CTE Research Network Equity Working Group and Postdoctoral Researcher, Neag School of Education at the University of Connecticut. See previous posts from the CTE Research Network Equity Working Group: Equity Framework for Research Design and Practice, and Using an Equity Lens to Design your Research

How can we look through an equity lens?

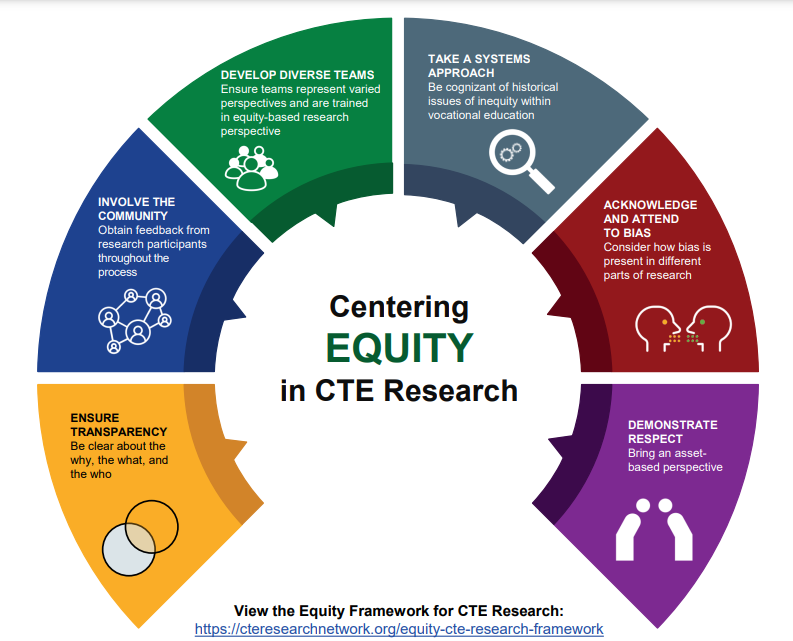

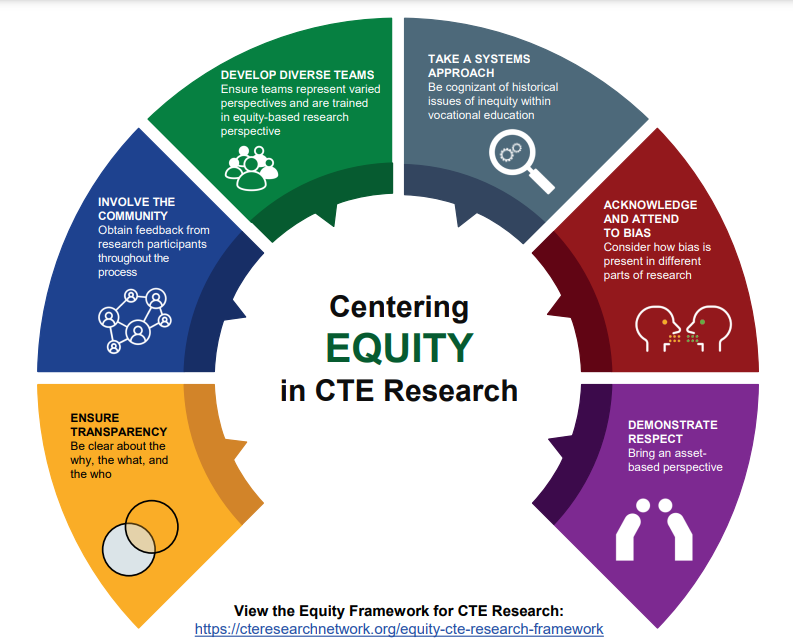

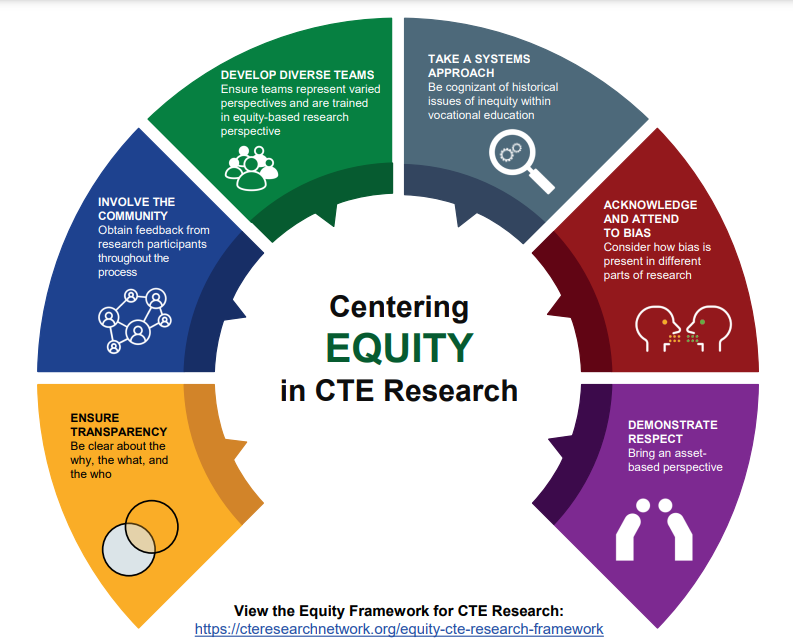

Educational researchers have the opportunity and responsibility to incorporate equity into the work they produce. To support that end, the Equity Working Group from the Career and Technical Education Research Network (CTERN) authored an Equity Framework for CTE Research which provides principles and practices for researchers on equity questions, designs, and implications throughout the research process. While this guide was authored with a specific focus on Career and Technical Education (CTE) research, the ideas within represent the expertise of a variety of experts in education research. Researchers from all social sciences could implement most if not all the recommendations.

Maintaining a focus on equity is important throughout the research process, and there are specific things researchers must attend to when considering measurement and data collection procedures to maintain rigorous research standards and ensure the safety of the population being studied. Whether the project is quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, non-empirical, or any other methodology which attempts to better understand the world of CTE, education, or social science writ large, there are three overarching principles researchers should consider when identifying, developing, and measuring data. These principles, described more fully below, are: a) consider and connect with the population being studied, b) practice critical meta-analysis with the measures selected for the project, and c) carefully attend to the safety of participants.

Consider and connect with the population being studied. CTE, and indeed all education policy, is locally implemented with potentially wide variations on multiple dimensions of student experience. An equity-focused researcher will make sure to attend to those wide variations throughout the process of selecting, designing, and implementing instruments and measures to ensure that the research captures the experience of the population with rigorous fidelity. To that end, connecting with local stakeholders throughout the process is an invaluable practice. This may mean asking stakeholders and/or participants to review instruments before rollout or to verify interpretations of previously captured administrative data.

Practice critical meta-analysis with the measures selected for the project. While not every researcher or team will take a critical perspective per se, there are elements of critical analysis that will benefit all projects. For example, if using previously gathered administrative data, an equity-focused researcher will both examine for and explicitly state the limitations and/or biases of those data throughout the measurement identification, analysis, and reporting stages of the project. Those limitations may be based on how the data were collected (i.e. who collects the data may impact responses), inherent limitations in the structure of the data (i.e. race/ethnicity being limited by which checkboxes were provided or that inappropriately center whiteness by presenting a “white as default” status), or variations in data accuracy that may be related to equity-related measures (i.e. an under-resourced institution may report less work-based learning (WBL) not because less is actually taking place, but because there are less available resources dedicated to the reporting).

A related measurement and collection practice that attends to issues of data limitation, particularly for posterity throughout the project, is the development of a “data dictionary,” in which researchers track metadata (or “data about the data”). Keeping a close record of definitions, mechanisms, and limitations about data – even if original data collection was not part of the project – can support researchers’ focus on equity during and after the project.

Carefully attend to the safety of participants. While all researchers should be interested in providing for the safety of their participants, these issues become even more important when working with historically disadvantaged or vulnerable populations for a variety of reasons. For example, the data being collected may be particularly sensitive in ways researchers may or may not be aware. Relatedly, minoritized populations are of greater risk of post-hoc identification if they belong to a comparatively low-sample subgroup. To address these issues, equity-focused researchers should minimize personally identifiable data when possible, and deidentify carefully and fully as early as possible in the measurement process. Further, equity-focused researchers should be careful to limit the scope of inquiry to only what is necessary for the research project to avoid undue burden and risk on participants.

While measurement and data collection procedures are often directly implied by the research design, the practices described above are ways in which an equity-focused researcher can continue to attend to issues of equity at this stage of the research process. While the above list is by no means exhaustive (see the full framework for additional details), they represent core ideas that researchers should consider when developing and implementing measurement. Similarly, these are a set of questions researchers can ask themselves and their teams regarding equity in the measurement and data collection phase:

Are the selected measurements aligned with the methodology and research design? Do the selected measures and tools require any modification to address issues of equity?

Has the research team effectively integrated community feedback into the measurement design and data collection processes? Has the team verified with stakeholders that the measures selected do in fact capture the experiences of participants with fidelity?

Has the research team critically examined the administrative data for inherent biases and addressed these biases in the analysis to the extent possible (including issues with bias arising from opt-out, measurement mechanics, or problematic differences in data collection)?

Did all participants have the opportunity to describe themselves from a demographic standpoint (if required)? If this is not possible (i.e. because of the use of administrative data), has the research team accurately and fully delineated that limitation?

Has the research team taken necessary steps to ensure the safety of their participants, including limiting collection to what is absolutely necessary and developing a data security plan in place that minimizes participants’ risk of exposure?

Is there flexibility in the data collection plan to account for unforeseen issues of equity that may arise?

There are a number of potential barriers to the above practices, including developing trust with stakeholders who may or may not be previously connected to the researchers, inherent limitations and/or biases when using existing administrative data, and the cost of original data collection (amongst others). Still, an equity-focused research team will engage with these barriers, both at the measurement/data collection stage and throughout the project, in order to better address the responsibility of social science research to ensure more equitable implementation of public policy.

Read this collection of multidisciplinary articles to explore epistemological questions in Indigenous research.